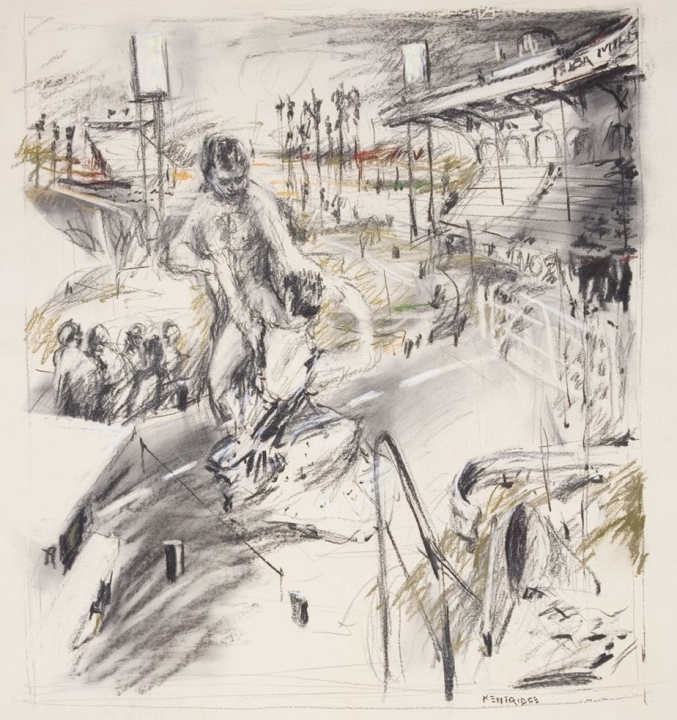

Highveld Landscape with Stadium

William Kentridge

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

signed

Notes

William Kentridge was awarded the Standard Bank Young Artist Award in 1987, during the period when this work was produced. After working extensively in theatre in the mid- to late 1970s, he went to Paris in the early 80s to study acting and directing at the École Jacques Lecoq. By the mid-80s he was working as an art director in the commercial film industry. Of the impact that these experiences had on his drawings, Kentridge has remarked:

One of the things I learnt was the way the space in which people moved - film space - was so completely arbitrary and changeable ... So the drawings that emerged from the film work had to do with the freedom that came from being able to play with space.i

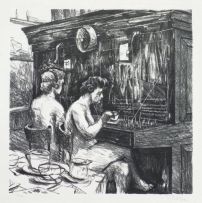

Works by German Expressionist Max Beckmann, Otto Dix and Käthe Kollwitz made a strong impression on him, both in terms of their expressive potential for social commentary and for their use of graphic media, in particular charcoal. Inspired by English satirist William Hogarth, he produced a body of drawings that comment on society and manners. They also refer to great art works he would have seen in Paris, like Watteau's Embarkation for Cythera, the inspiration for The Embarkation, with which this work has much in common.

A handrail in the foreground invites us to step into the picture. It suggests the steps of a swimming pool, which Kentridge used throughout the 80s as a trope for a particular South African lifestyle. It also resembles the portable steps that continue to feature in his works and that played a significant role in his lecture performance, I am not me, the horse is not mine, which formed part of Kentridge's process of developing his celebrated production of Dmitri Shostakovich's The Nose for the Metropolitan Opera House, New York in 2010.

Beyond the middle ground which suggests various outdoor leisure activities such as camping, an empty stadium frames a Highveld landscape as if it is the main event, albeit a contested one. Unlike the tradition of South African landscape art, Kentridge provides an essentially urbanised view of the landscape defined by structures and objects that provide evidence of human intervention and habitation.

i Geofrey V. Davis and Anne Fuchs, eds., Theatre and Change in South Africa, Harwood Academic Publishers, Amsterdam, 1996, page 141.