Important South African and International Art

Live Auction, 10 November 2014

Harry Lits Collection

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

signed

Notes

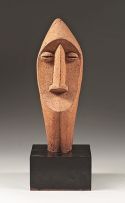

Sydney Kumalo was a still a teenager when, in 1952, he began attending biweekly art classes at a hall designated for "non-European" adult recreation on Polly Street in central Johannesburg. Led by Cecil Skotnes, the loose curriculum focussed on drawing, painting and basic aspects of sculpture using brick clay. Sophiatown-born Kumalo, whose interest in art was sparked by youthful encounters with paintings and sculptures seen in white suburban homes serviced by his house-painter father, concentrated on painting. Despite his lack of formal training and youth (Kumalo was nine years younger than Skotnes), his arrival at Polly Street helped establish a "contemporary creative climate", according to Walter Battiss. Writing in a 1965 issue of the London magazine Studio International, Battiss remarked how Kumalo, with his "talent" and "brain", helped Skotnes to breath "new life" into the centre.1 The death of Kumalo's father prompted his sudden transition from painting to sculpture. "He was a watercolour painter and needed a job," recalled Skotnes in a 1984 interview.2 On the same day that Kumalo announced his plight to Skotnes, the Bishop of Kroonstad visited Polly Street in search of an artist to paint the ceiling mural at St Peter Claver Church in Seeisoville, Kroonstad. Skotnes proposed Kumalo. The pair jointly executed the mural, Kumalo additionally producing bas-reliefs of the 14 Stations of the Cross. Skotnes showed photographs of the latter to Edoardo Villa, who in 1958 agreed to mentor Kumalo twice a week at his studio. Kumalo's earliest sculptures, of which this reduced portrait is a fine example, were made from brick clay, which was easy to obtain and inexpensive.3 The work reveals the early generic influence of West and Central African sculptural idioms on Kumalo, whose syncretic style was also greatly influenced by the volumetric experiments and simplifications of the human form by modernist sculptors like Brancusi and Moore.

1 Battis, Walter (1965) 'Cecil Skotnes and the Angst of Africa', Studio International, Vol. 170. Page 124.

2 Skotnes, Cecil (1984) Interview with Cecil Ambrose Brown, 20 April, Cape Town.

http://cecilskotnes.com

3 Rankin, Elizabeth (1996) 'Teaching and Learning: Skotnes at Polly Street', in Cecil Skotnes, Cape Town: Cecil Skotnes. Page 71.

Illustrated:

Peffer, John (2009) Art and the End of Apartheid, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Page 28.

Literature

Peffer, John. (2009) Art and the End of Apartheid, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Illustrated on page 28.

Miles, Elza. (2004) Polly Street: The Story of an Art Centre, Johannesburg: Ampersand Foundation. Another example from the edition illustrated in colour on page 84.