Important South African and International Art

Live Auction, 12 November 2018

Evening Sale

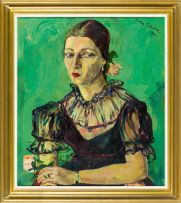

About this Item

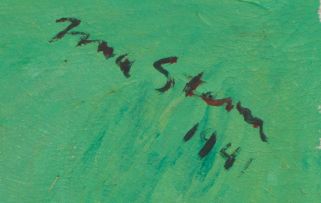

signed and dated 1941

Notes

The subject of this elegant portrait is Mary Cramer (née Ginsberg, 1912-1988), the younger sister of Irma Stern's friend and confidante, Freda Feldman. Although it has some of the formal characteristics that we associate with Stern's work in this genre - not least the vigorous impasto describing both form and detail - the portrait is uncharacteristically restrained for Stern. Like two other portraits painted during the early 1940s, Argentinian Woman (1941) (fig. 2) and Portrait of Stella, Lady Bailey (1944) (fig. 3) the painting also has something of a Spanish air.

Photographs of Mary taken around the time this portrait was painted show that she wore her hair with a centre parting (fig. 1), but when combined with the flower behind her ear and the black dress with its transparent chiffon top with puffed sleeves and ruched collar, the Spanish reference is intensified. In effect, the painting is evocative of Goya's portraits of noblewomen, particularly those of the Duchess of Alba. The Spanish references in these paintings may reflect something of Stern's nostalgia for Spain at the time (her travels had been curtailed by the war in Europe, and she had not visited the continent since 1937), while they also create a sense of drama that puts the sitters outside of the constraints of everyday life.

Mary was the second daughter, after Freda (who was 15 months her senior), in a family of ten children. Mona Berman, Freda's daughter, notes that, 'Where Freda was outgoing, self-reliant and charismatic, Mary was shy, reserved and inward looking. But despite these differences, they complemented each other and were seldom apart.'1 Indeed, so often was Mary at the Feldmans' Houghton home that Mona speaks of Mary, who was childless, as a second mother, intimately connected with her childhood.

Irma Stern was also a frequent visitor at the Feldmans during the 1940s and 50s, and Freda would go to considerable lengths to ensure that the artist's considerable physical and practical demands were met, including painting the dining room walls a specific shade of emerald green at her behest, the better to offset her paintings. Compelled by Freda's elegant appearance and gracious demeanour, Stern produced a number of portraits of her, including four oils (three of which were recently sold by Strauss & Co.), several charcoal drawings and a gouache. In 1941 Stern spent an extended time at the Feldmans during which time, as Mona recalls, 'She painted many subjects, including the portrait of my mother in her model French hat and the portrait of Mary in her stylish black dress.'2

Mary, who was 29 years old when the portrait was painted, was, according to Mona Berman, 'the most beautiful of all the sisters. She had classic features - a wide forehead, clear blue-green eyes, an aquiline nose and well-formed lips … She had impeccable taste and dressed in stylish but modest clothes … she looked like a Vogue model.'3 Indeed, Stern has made much of Mary's alabaster skin, fine features and poised bearing in this portrait; the severe centre parting of her swept-back, chestnut hair perfectly framing her face and offsetting the glistening vermilion of her exquisitely painted lips, set dramatically against the emerald-green backdrop.

The sitter's graceful poise is enhanced by Stern's careful depiction of the details of her accessories: a pink rose holding her hair tightly in place, an elegant drop-pearl earring, a slim black-and gold wristwatch on her slender wrist, and three black-and-gold rings adorning the ring finger of an immaculately manicured hand, which in turn holds a pale orange rose. While these details are clearly markers of gender and social standing there is something disquieting about the painting that makes them seem like talismans, there to protect the exquisitely vulnerable young woman rather than to adorn her. 'Her quiet reserve and aloof manner created an aura of mystery around her that discouraged intimacy,'4 says Mona, and it is this enigmatic air that Stern has uncannily captured. To the outside world, Mary appeared to lead a charmed life. She was beautiful and married to a successful man who adored her. She lived in a lovely home with a fine garden and was a gracious hostess renowned for her attention to detail and exquisite taste. Yet inwardly, it seems that Mary was driven by passions and torments of which she never spoke. 'Something about her always remained a mystery,' says Mona, 'clouded in conjecture and uncertainty.'5 Stern certainly captured Mary's exceptional beauty and grace, but more than that, she produced a compelling portrait of a complex, secretive woman.

There is a pensive aloofness in Mary's expression that speaks also of a certain pathos. While the slight exaggeration of her limpid eyes immediately draws the viewer, this is deflected by her refusal to return the gaze; she stares instead into the middle distance beyond the frame. While she is certainly poised, she seems somehow emotionally tense, the pearl earring a metonymic displacement, perhaps, of an invisible tear.

Freda hung the work in pride of place in the emerald-green dining room with the portraits that Stern had painted of her. Stern, always the master of expression, presciently captured something of the quiet, unvoiced turmoil of Mary's life, and in so doing gives us an extraordinary portrait of the complexities and contradictions that lie beneath the masks of outward appearance. Federico Freschi

1 Mona Berman, personal communication, 22 September 2018.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

Literature

Mona Berman (2003). Remembering Irma: Irma Stern - A Memoir with Letters, Cape Town: Double Storey, illustrated in colour on page 166.

Standard Bank Gallery (2003). Irma Stern: Expressions of a Journey, Johannesburg: Standard Bank Gallery, illustrated in colour on page 81.