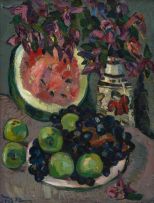

Lady of the Harem

Irma Stern

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

signed and dated 1945

Notes

Painted during her second trip to Zanzibar in 1945, Woman of the Harem is typical of something of a shift in Stern's approach to her subjects at this time. As she put it in a letter from Zanzibar to her friends Freda and Richard Feldman, 'I am painting dramatic pictures, compositions and faces - not just types and races.'1 This sense of a shift towards a deeper engagement with her subjects is reiterated by Joseph Sachs, writing in 1942, who suggests that Stern's Zanzibar paintings are the 'high water mark of her art. Canvases are full of gorgeous colour and the strange mysterious atmosphere of this tropical island, but they have also recaptured the spirit of the diverse humanity that is found on the East Coast of Africa.'2

It is important to remember, however, that Stern was a product of her time. Her approach to her subjects was informed by her early training in German Expressionism, where the notion of the 'primitive' (particularly of non-Western cultures) was upheld as something of an article of faith; a way of asserting a fundamental, utopian humanism as a means of countering the dehumanising forces of twentieth-century industrialisation. In these terms, Stern's images of the exotic 'others' - problematic as they may be when viewed through the lens of postcolonial theory - offer insights that might otherwise have been lost and leave us with a compelling visual legacy of vanishing ways of life that might otherwise have gone unrecorded. As Marion Arnold puts it, 'Her portraits of black models make assumptions about life style and sometimes, unwitting on her part, telling social comment is rendered.'3

Stern was captivated by the romance and exoticism of Zanzibar, which she saw at once as a cosmopolitan melting pot of cultures and as expressive of a particular kind of spirituality. In a 1954 article, Stern describes being transfixed by an old Arab bead seller, who seemed to live 'in a world of his own, a spiritual world, untampered by travels and noise and desire for money or goods … In this I found a new truth - a truth from early times and handed down from age to age, a worship of spiritual forces.'4 At the same time, however, she could not avoid remarking on gender inequalities, particularly as regards the Arab community. 'Arab women are still in purdah,' she writes in Zanzibar, 'and only deeply veiled may they leave the house.'5 She describes visiting the luxurious, mysteriously exotic and exclusively feminine world of the harem, 'filled with their dowries of lovely old eastern silks with heavy gold fringes, trousers ruched at the ankles with the frills falling over their feet. Heavy perfumes hanging in the air - expensive, penetrating Eastern perfumes. The large mirrors in heavy golden frames coming down from the ceiling and decorated with arabesques and crests are gifts from the Sultan. The rooms are laid out with mats over old dark red tiles - Persian mats and straw matting in vivid array. In front of the bed is a mattress in red silk with heavy stripes of gold brocade edging it - the day bed.'6

In this painting, the intense, jewel-like colours of the woman's garments, the way in which she fills the composition, and the inscrutability of her half-opened eyes convey something of this languid mystique and intimacy. Positioned near an open window that is partially covered with a wroughtiron screen of decorative arabesques, the painting is reminiscent of Matisse's odalisques painted during the 1920s. However, the comparison does not go much further than certain formal similarities. Matisse's odalisques were modernist essays in an established orientalist trope: the erotic harem fantasy featuring exotic, dark-skinned women from France's North African colonies as passive fetishes of the eroticised male gaze. While Matisse claimed to have seen harem women during his trips to Morocco in 1912-13, it is improbable that he would have had access to these severely restricted spaces and was more likely to have encountered their simulacrum in the local brothels. His odalisques remain, therefore, decorative cultural stereotypes.

Stern, on the other hand, paints with an urgency born of a desire to convey her charged impressions of the intimate, feminine space, and in so doing to give a sense of the vital, colourful presence of what lies behind the veil. 'In this Eastern world the woman has no rights,' she concluded in Zanzibar. 'They run about like ghosts, black, with their Jashmak [sic] covering their faces and bodies. Each nation of the East has a different way of hiding their females.'7

Federico Freschi

1 Quoted in Mona Berman (2003). Remembering Irma: Irma Stern - A Memoir with Letters, Johannesburg: Double Storey, page 97.

2 Joseph Sachs (1942). Irma Stern and the Spirit of Africa, Pretoria: Van Schaik, page 61.

3 Marion Arnold (1995), Irma Stern: A Feast for the Eye, Cape Town: Fernwood Press, page 101.

4 Irma Stern (1954). National Council of Women (NCW) News, page 8.

5 Op. cit., page 12.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid., page 45.

Literature

Irma Stern (1948). Zanzibar, Pretoria: Van Schaik, illustrated in black and white on page 14.