Important South African and International Art

Live Auction, 13 November 2017

Session Three

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

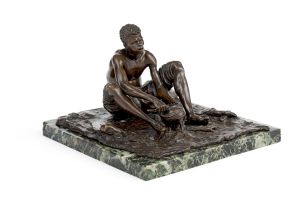

About this Item

Notes

Ernest Mancoba inscribed his sculptures with E Mancoba, Ernest Mancoba, E M, N E Mancoba and R Mancoba (Ro…). The first three are self-explanatory, the two remainders not.

A Shangaan praise-singer, who was a fellow mineworker of the artist's father, Irvine, visited the Mancobas at their home on the East Rand to pay his respects to the parents and their first born. When he saw the baby he called out 'Ngungunyana!' and chanted the praises dedicated to the great chief of the Shangaans, Ngungunyana. He asked Irvine to call the boy by that name. Unfortunately the infant had already been christened Ernest Methuen Mancoba. Nevertheless the Shangaan name stuck and at the training college at Grace Dieu schoolgirls referred to him as 'king of the Shangaans'.

In 1932, on completion of the sculpture St Augustine of Canterbury for the Church of Saint Augustine in Belvedere, Kent, England, Mancoba inscribed N E Mancoba on the base of the piece. Thus he acknowledged his African name and reconciled two perspectives: African and Occidental.

R Mancoba (Ro…) refers to Ronald - called Ronnie - the artist's younger brother and last born (c.1922) of Irvine and Florence Mancoba's seven children. In 1934 - two years prior to the making of Head - Mancoba carved a double portrait of two boys: Ronnie and his friend. Mancoba recalled they were not keen on posing; eventually he persuaded them with the promise of sweets on completion of the piece. He significantly entitled the carving The Future of Africa (also documented Africa to be and Future Africa). Similar to St Augustine of Canterbury this piece was carried out in the typical, true-to-nature style of the period.

Whilst in Cape Town in 1935 Mancoba befriended Lippy Lipschitz who recommended that he acquaint himself with Negro Primitive Sculpture, the seminal text on the classic art of West and Central Africa by Guillaume and Munro. Mancoba, inspired by the images and text, internalized the contents. Subsequently, he freed himself of the naturalistic viewpoint he had followed in his previous carvings. Inspired, he carves Faith in 1936 (whereabouts unknown) and Head (Lot YY) which both exemplify the African Renaissance in his oeuvre.

Head reinterprets the features of the two boys who posed for Future Africa into a kind of African mask expressing unutterable sorrow. In an interview of 1938 Mancoba observed: 'My carvings are made to show Africa to the white man. That is why they are sad'.1

By reinterpreting the mood of the two boys as expressed in Future Africa in a masklike African manner the artist dedicates Head to his brother Ronnie, inscribing it R Mancoba (Ro…).

The provenance of Head is most interesting. When Mancoba returned to the Rand from Cape Town in 1936 he carried a letter of introduction written by Lipschitz to the sculptress Elsa Dziomba (1902-70). Mancoba looked her up in her studio, presented the letter and they became friends. When Mancoba decided to further his art studies in Paris she was among the referees supporting Mancoba's application of a loan and grant of 100 pounds sterling from the Bantu Welfare Trust. Mancoba highly regarded Dziomba's art. Before he left for Europe in 1938, in acknowledgement of their friendship, he gave Head to her. Many years later Dziomba told her friend Hermien Domisse McCaul that she knew the gifted Ernest Mancoba who left for Paris to study art and she gave Head to her friend. A year before Dziomba died Domisse wrote an in-depth article on Dziomba's art for the December 1969 edition of Artlook. When Domisse McCaul learned that the Johannesburg Art Gallery was hosting Hand in Hand, a retrospective exhibition of the art of Ernest Mancoba and his Danish wife Sonja Ferlov, she informed the gallery of the piece she held and without any ado Head was collected and included in the show. Within the context of the collection of carvings by Mancoba for Hand in Hand the importance of Head cannot be over-emphasized. Owing to the fact that the whereabouts of Faith is unknown, Head is the earliest carving so far located, showing Mancoba's breach with the naturalism of his earlier representations. This piece, expressing the spirit of Africa is a benchmark within the South African context.

To attend the opening of Hand in Hand in 1994 Mancoba visited South Africa for the first time after his departure in 1938. His son Wonga (1947-2015) accompanied him; Sonja Ferlov his wife died in 1984.

McCaul, who only knew of Mancoba through Dziomba, was keen to make his acquaintance and invited him and his son to an afternoon tea at her home in Auckland Park. They enjoyed a memorable afternoon and reminisced about their mutual friend, Dziomba, Greek drama and philosophy as well as Shakespeare.

Elza Miles

1 See Elza Miles (1994), Lifeline out of Africa, Cape Town: Human and Rousseau, p.34.

Provenance

A gift from the artist to Elsa Dziomba

Exhibited

Johannesburg Art Gallery, Johannesburg, Hand in Hand, 1994-1995.