Important South African and International Art

Live Auction, 13 November 2017

Session Three

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

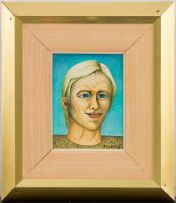

About this Item

signed and dated 44

Notes

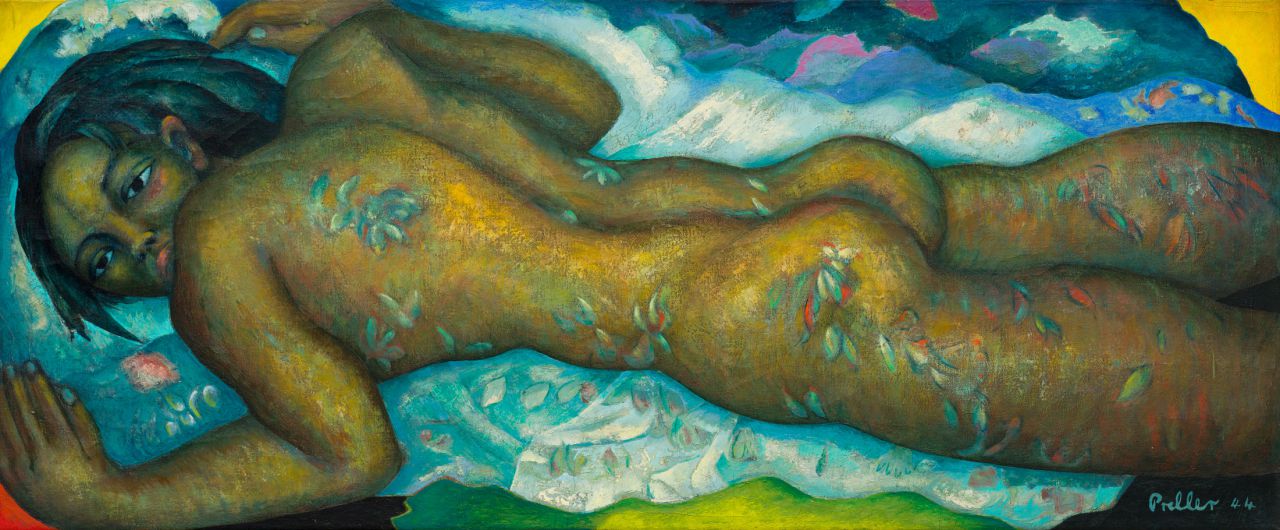

This iconic work, Fleurs du Mal (1944), was often included in Esmé Berman's public lectures when she was presenting and discussing Alexis Preller. While Berman and I were researching works for the Preller double volume publication, we were unable to track down and photograph this work, and were later informed that it was tragically lost in a fire. This necessitated our inclusion of an older, yellowed image of the work. The surprise of the recent emergence of Fleurs du Mal was thrilling and a relief that it had in fact not been destroyed. The revelation of its true colour again reinforces Preller's reputation as a colourist.

Fleurs du Mal, painted in 1944 in direct response to his war experiences, is a striking record of his ability as an artist to process significant moments in a highly personalised manner. Preller had enlisted in 1940 to serve in the South African Medical Corps and had left for Egypt by boat, which travelled up the east African coast in April 1941. Preller chose not to be an active protagonist within the war but to serve and tend those injured in the cross-fire on the front lines. This saw him actively positioned with the medical corps as a stretcher-bearer in the north African campaign, positioned at the hotspots of Helwan, Mersa, Maltruh, El Alamein, Sidi Omar, Sidi Rezegh and Tobruk.

Preller was finally captured in June 1942 and sent as a prisoner of war to Italy. He was later moved to Egypt and finally returned to South Africa in1943 on a troop ship, again voyaging down the east coast of Africa.

This work Fleur du Mal painted a year later after his return reflects his seriousness as a painter and his need to re-engage with the interrupted life he had left behind. His works eloquently embody his attempt to translate, integrate and transform his war experiences into a group of works which included Remembrance of Things Past and Prisoner of War, both painted in 1943. Both these works were included on his Johannesburg exhibition at the Gainsborough Gallery in June 1944. The exhibition was opened by the poet, Uys Krige.

Esmé Berman, in recounting the genesis of Fleur du Mal, describes how his memories were very real. They encompassed images of brutally shattered bodies, but also included acts of huge compassion and the exercise of healing, to which he was a witness. The horror of pain was transformed by the transcended beauty of merciful repair. In his mind, the gauze swabs inserted into the shrapnel wounds took on the appearance of butterflies that had settled for a moment on the tortured flesh; and when he began to give artistic expression to wartime images that haunted him, he attempted to convey that paradox of beauty in the midst of horror.

Western convention tended to restrict portrayal of the male nude body to allegorical scenes of gods and history. Even so chaste an image of a nude young man may have appeared provocative. Thus, Alexis Preller avoided defining the gender of the androgynous figure. He transformed the gauze swabs of his memory into flowers scattered across the iodine-painted torso, and he borrowed French poet Charles Baudelaire's literary title, Flowers of Evil.

Preller's transformation of these painful wounds inflicted by the evils of war into poetic blooms represent a redemptive and healing act, both in his caring capacity as a medic in the tented operating theatres of the desert, and later in the solitary capacity as artist.

Spirit of the Dead watching Manao Tupapau, Paul Gauguin's startling work of 1892, was inevitably the inspiration for Preller's Fleurs du Mal. This painting is one of the earliest and most significant of his works to be influenced by Gauguin, who was to be an inspiration to Preller's thinking and work over a lifetime.

In both the Preller and Gauguin works, the fluorescent flowers, decorative cloths and a figure set across the horizontal format, create an eerie and otherworldly quality. Both faces reflect a fear and vulnerability, and the paintings evoke an ethereal quality set off against the sheer physicality of the recumbent human form.

The fearful face engaging the viewer in Preller's painting emerges from behind a broad shoulder. The startled almond-shaped eyes, broad forehead, straight nose and soft vermilion lips, cheekbone and ear are framed by the sharply pointed hair hanging down on one side. In contrast above a full body of hair echoes back, almost landscape-like, into the background. The undulating cloth upon which the young person's body with the painfully swollen legs lies appears to transform, in the distance, into snowcapped mountains of the imagination or delirium, receding into the darkness.

The four corners of the work are painted bright yellows, red and black, alluding to the eroded edges of Gauguin's famous work, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897). These punctuating edges work like quotation marks alluding to the psychological and philosophical quests posed by Gauguin's artistic pursuit and his sense of engaging extremity.

In this early powerfully poetic work, Fleurs du Mal, his tragic rendition of this damaged young man is a precursor to the leitmotif of the male nude in his oeuvre. The male nude plays out in many symbolic semblances: Adam, Apollo, David and Sebastian, all appear in different embodiments. These culminate in the empowered and transcendent male forms derived from the kouroi, the 5th century BC Greek marble sculptures. These heroic and iconic torsos are seen in Preller's final triumphant Marathon works of the 1970s. On a profound level, they reflect a self-realisation for Preller himself, both as a man and an artist.

Metaphorically Preller seems to have engaged on a long journey, the vulnerable and damaged young man lying prone on the edge of the battlefield in Fleurs du Mal is a far cry from the transcendent Marathon images of his late works.

Karel Nel

Image required for text:

Paul Gauguin Spirit of the Dead watching Manao Tupapau (1892)

Exhibited

MacFadyn Hall, Pretoria, 1946.

Pretoria Art Museum, Arcadia Park, Alexis Preller Retrospective, 24 October 1972 - 26 November 1972, catalogue number 13. Illustrated, unpaginated.

Literature

Alexis Preller Retrospective, Pretoria: Pretoria Art Museum. Illustrated, unpaginated.

Esmé Berman and Karel Nel (2009). Alexis Preller: Africa, the Sun and Shadows, Johannesburg: Shelf Publishing. Illustrated in colour on page 71.

Esmé Berman and Karel Nel (2009). Alexis Preller: Collected Images, Johannesburg: Shelf Publishing. Illustrated in colour on page 18.