Important South African and International Art

Live Auction, 13 November 2017

Session Three

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

inscribed with the artist's name, date 2007, medium and the title on a Marian Goodman Gallery, New York label adhered to the reverse

Notes

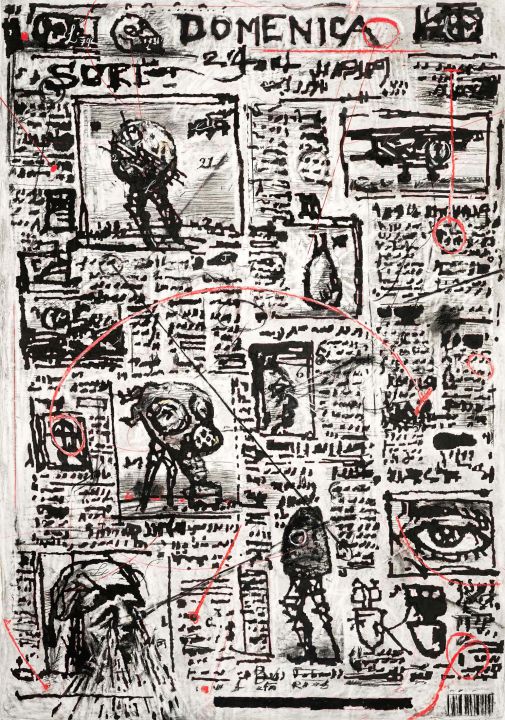

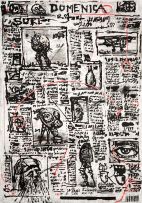

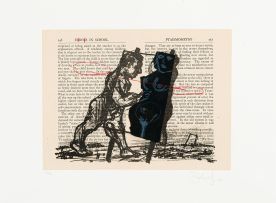

William Kentridge was working on one of his stop-frame animation films, What will come has already come (2007), dealing with the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in the 1930s, when he received an invitation to do drawings for the front page of the cultural magazine accompanying the weekend edition of the Italian financial paper, Il Sole 24 Ore. Paging through back copies of the magazine, Kentridge was struck by the space devoted to Old Masters and to covering large scale restoration projects of the Italian Renaissance artist Giotto, and the most famous artist of the Italian baroque period, Carravaggio. The five drawings which emanated from this commission, of which the present lot is a prime example, combined visual elements of the chemical warfare the Italians used against the Abyssinians, such as gas masks, and images referencing the work of the old masters, such as Giotto's The Massacre of the Innocents (1305), at bottom left of the drawing. The Massacre is a biblical story, but Kentridge notices a clear similarity between this image and the victims of dead Kurdish villagers in the Middle-East. Since he could not find any actual images of the effect of the chemical warfare in Ethiopia at the time, the image of a crying mother suffices in his mind as relevant and applicable to the victims in the Horn of Africa as well.

The form of the drawings was dictated by the shape and scale of the sheet of newspaper they would be printed on, and by the quality of the printing normally associated with newsprint. Large-scale drawings seemed to be the ideal choice in which detail could be captured and then later reduced to tabloid size. In addition, he was fully aware of the role images play on the front page of a newspaper, and hence adapted very strategic positioning of the visual elements that complemented the 'verbal' ones, or the text itself, which Kentridge ironically renders illegible, the implication being that history is often obliterated from the records and from public memory.

Kentridge, however, quickly abandoned working on a large scale, and instead worked on a series of small sized etchings to generate the five images, which he then later enlarged into the present format of the drawing, approximately eight times the size of the newspaper. When he made the present lot, Kentridge used a very soft Korean paper and included embossing, carried out using a blunt instrument pressed into the paper, and then he applied poster paint for the intense black areas, supplementing these with charcoal and pastel, and erasing certain parts. The large-scale drawings were then used to make the plates for newspaper printing.

The most recent iteration of Kentridge's interest in Italian history is to be found in the majestic project on the banks of the Tiber river flowing through the heart of Rome, in which he captures scenes from Italian history, specifically those pertaining to Rome, by means of applying a stencil to the grime on the walls of the river bank, and spraying the stencil with high pressured water hoses, laying bare the negative spaces which create the final image.

Literature

A similar drawing is illustrated in Lilian Tone (ed) (2013) William Kentridge: Fortuna. Thames & Hudson, p85.