Important South African and International Art

Live Auction, 13 November 2017

Session Three

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

signed and dated 79; signed, dated and inscribed 'Spain' on the reverse

Notes

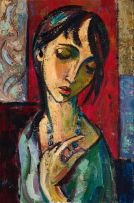

Christo Coetzee's formidable work, Forma Decorem, is a prime example of his interest in portraiture. It constitutes a fulcrum between the numerous portraits of brides he painted in the early years of his career, after his studies at Wits in the late-1940s, and the hundreds of facile portraits on paper rendered in linear profile in the 1980s and 90s.

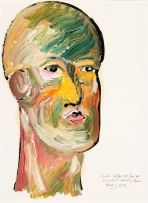

Coetzee abandoned portraiture for much of the 1960s and 70s and pursued a more abstract, non-figurative style in his work, largely due to his exposure to contemporary abstract expressionist trends in Europe, employed by such artists as Georges Mathieu, Lucio Fontana and Alberto Burri, as well as by members of the Gutai Artists Association, a movement in post-war Japan.

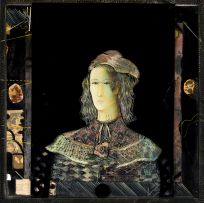

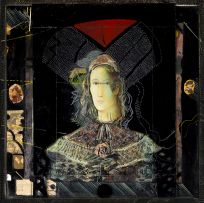

In Forma Decorem, however, Coetzee creates a veritable inventory of art historical concepts and ideas that are all spliced together in this singular, angelic portrait. He includes Byzantine angels in collaged form on the frame, as well as references to Renaissance portraiture, and even to the famous Dutch 17th century portrait tradition by satirically using a cut-out image of the famous Rembrandt self-portrait from a popular cigarette brand at the time in this work.

Not only does he reference the Renaissance interest in the study of Mathematics and Astronomy, as is evident in the numerous equations embellishing the portrait, and the orbs surrounding the sitter's face, but he also suggests wider cultural-historical traditions of the Italian performance and dramatic arts by invoking the Commedia del Arte stock character of the Pierrot in the dress of this sitter. In addition, Coetzee suggests something of the science of perspective, closely associated with the painting of the Renaissance, by using many diagonal lines which criss-cross the picture plane. Coetzee frames the portrait numerous times, from his own hand-painted frame, to no fewer the five other framing devices or suggestions of borders surrounding the portrait.

One of the most interesting and novel aspects of this portrait, however, is that the picture plane is obscured by a sheet of painted plexi-glass that is affixed on top of it. It obscures the identity of the sitter and at the same time, provides an additional, if embellished, one. The plexi-glass can be reversed, or turned around, encouraging ongoing viewer participation, and provides different perspectives on the portrait: the one, by means of the painted eyes on the Perspex which are reflected on the actual painting, effectively adding an additional pair of eyes; the other side, emphasizing the locks of hair of the sitter.

'What could be more compelling in our time than this angel with its incomprehensible face?' Coetzee observed in the catalogue notes to an exhibition, Tableux Peintures, at the Rand Afrikaans University in 1987. It is certainly the case with this portrait. He also invokes the word, 'iudicum', meaning a form of self-assessment of what the artist has produced, and in terms of that, the title of this portrait, Forma Decorem appears somewhat ironic, given all the various ways Coetzee deconstructed the conventions of portrait painting in this work.