Contemporary Art

Live Auction, 16 February 2019

Contemporary Auction

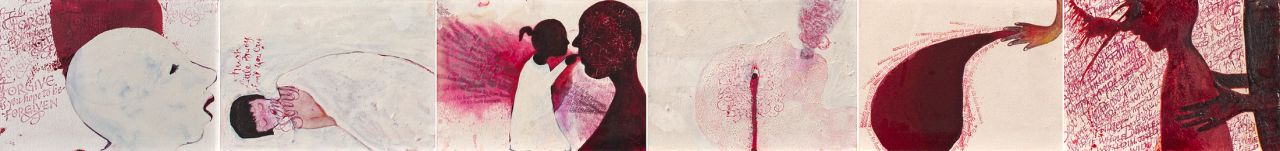

About this Item

each signed and dated 2003 on the reverse and inscribed with the artist's name, title, date, medium and dimensions on a Goodman Gallery label on the reverse

Notes

'Shame is part of conflict, and current global conflicts have reinserted a sense of shame onto the public stage. However powerfully shame is recognised and represented, it has neither a single face nor a common language. It exists rather in fragments - in cultural detritus left over from unexpected trauma, and in the imagined spectres of the fear, loathing, loss and fright, which surface in our visual cultures in the wake of traumatic woundings. Mostly these spectres show only the merest traces - intense feelings captured in fleeting shapes, textures and colours.

Shame involves psychological nakedness, exposure, humiliation, hurt and deep embarrassment. When shamed, we lose our dignity and integrity in full view of others. But in South Africa, to say 'shame' is also to express sympathy for, and identification with, someone else's public pain. If you should fall in the street people, for instance, might exclaim 'shame' or cry out 'sorry', even though they are not to blame for your fall. The Afrikaans version of this crying out at hurt is 'siestog', tellingly translated - in my mind - as a mixture of disgust (sies) and pity (tog).

In the recent South African past, shame has been dramatised and confronted as a state of hurt and complicity in the hurt of others. Our Truth and Reconciliation Commission staged hurt and complicity in public shows of shame, expressed in the languages of human suffering, apologetics, confession, protestations of good faith, exposures of bad faith. After this historical moment all sorts of stories have emerged which bespeak the state of shame, which connect the most public of political events to the most private and intimate of individual experiences.'1

- Penny Siopis. (2016) Shame, Cape Town: Stevenson. Pages 7 and 8.

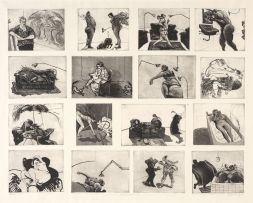

Literature

cf. Sophie Perryer (ed.) (2004) 10 Years, 100 Artists: Art in a Democratic South Africa, Cape Town: Bell-Roberts in association with Struik. Other examples from the series are illustrated on pages 348 and 349.

cf. Gerrit Olivier (ed.) (2014) Penny Siopis: Time and Again, Johannesburg: Wits University Press. Other examples from the series are illustrated on pages 154 and 155.