Important South African & International Art, Decorative Arts & Jewellery

Live Auction, 16 March 2015

Important South African and International Art Evening Sale

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

signed and dated '91

Notes

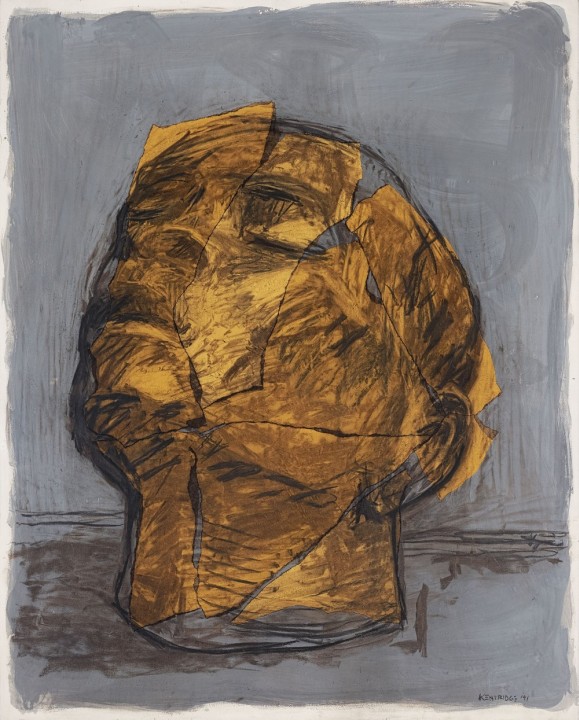

The human head is a recurring motif in William Kentridge's artistic output from the late 1980s and early 90s. The origin of his interest in this particular subject can partly be traced back to a three-month stay in Tuscany in the late 1980s. During his sojourn Kentridge visited the Basilica di Santa Croce, a Franciscan church in Florence noted for its Giotto frescoes, where he produced a series of sketches. In 2006 Kentridge recalled how he later cut up his Giotto drawings to rearrange the figures, "and had on the studio floor dismembered fragments of bodies and heads, waiting to be reconstituted".1 During his extended stay in Italy the artist also saw an exhibition or work by the British sculptor Tony Cragg featuring a series of bronze casts of beetroots with crude faces carved into their surface. These and other sensory influences were later distilled into his well-known drypoint etching, Casspirs Full of Love (1989), an almost museological display of severed heads in a shelf-like box.

A prolific artist whose work spans a range of media, Kentridge in 1991 produced two new animated films, Mine and Sobriety, Obesity and Growing Old, the latter awarded the Rembrandt Gold Medal at the 1991 Cape Town Triennial. Mine is notable for its violent subject matter. The opening sequence of the film lingers on a charcoal-drawn head that resembles both a miner wearing a lamp in a dark underground work environment and crowned Ife head from Nigeria displayed on a plinth.2 The head at the start of Mine also bears a striking resemblance to the severed heads in a landscape depicted in the etching, Reserve Army, from the portfolio Little Morals, which are both a quotation and update of the heads in Casspirs Full of Love.

The work offered here forms part of this lineage, but is also noticeably different.

In 1991 Kentridge exhibited five large heads at the Newtown Galleries in central Johannesburg. These large collage works, which incorporated figure-defining charcoal marks and colour-field gouache landscapes, were shown with 40 smaller studies, some full figured, others focussed only on the head. The stylistic traits of this work, which is explicitly quoted in a later hand-coloured drypoint etching titled Head (1993), is noteworthy for several reasons. Commenting on the form of his drawings from this period, art historian Michael Godby notes Kentridge's "disdain for detail and finish", the "absence of precise identity" in his figures and general use of "types to represent classes or sections of the population".3 This formal reading is important when considering the genre to which this portrait study is allied.

The severed head is a stock motif of art history, with examples dating back to the Palaeolithic period. Kentridge's head, here neutrally presented as an object of contemplation in a uniform grey landscape, avoids the grotesquery typically associated with historical and contemporary artistic portrayals of severed heads. It does not indulge in what Bulgarian-French philosopher Julia Kristeva, in her book The Severed Head, calls the "power of horror".4 Isolated and disembodied, Kentridge's gestural anatomical study is compelling but not grotesque. Rendered in generic rather than specific detail, it is a monumentally scaled affirmation of the head as locus of being and perception, an affirmation too of sentience in the face of horror.

1. Kentridge, William (2006) William Kentridge Prints, Johannesburg: David Krut Publishing. Page 36

2. Christov-Bakargiev, Carolyn (1998) William Kentridge, Brussels: Société des expositions du Palais des beaux-arts de Bruxelles. Page 60

3. Godby, Michael 1992) William Kentridge, Drawings for Projection, reprinted in Christov-Bakargiev, Carolyn, op.cit. Page 166.

4. Kristeva, Julia (2012) The Severed Head, New York: Columbia University Press. Page 102