Important South African & International Art, Decorative Arts & Jewellery

Live Auction, 16 March 2015

Important South African and International Art Evening Sale

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

signed, dated 1995/6 and inscribed with the title and the medium on the reverse

Notes

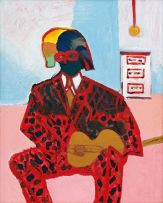

Around the middle of the last decade of the 20th century, Robert Hodgins produced a series of paintings linked together by powerfully expressionist colour usage. Oils on canvas for the most part - as opposed to the less plastic acrylic and tempera on board that he had explored in the 1980s - the paintings are also characterised by broadly literary references in titles that evoke British and/or European events and institutions. In this way Hodgins took as titular subject the madhouse at Bedlam, the gallows at Tyburn,1 and, in the 1995-6 work currently at auction, the so-called Dreyfus Affair.

A gobsmacking miscarriage of justice recently turned into an award-winning 2013 novel titled An Officer and a Spy, by author Robert Harris, the frame up of Jewish cavalry officer Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a hundred years earlier (1894) for passing on military secrets to militaristic and expansionist Prussia was at the same time a cause célèbre in the Third French Republic and a virtual acid test of the public values and justice in post-Enlightenment Europe.

As was passionately argued by Emil Zola, the pre-eminent French novelist of the day in a front page 4500 word open letter under the headline J'Accuse…, the conviction of the Jewish Dreyfus on manufactured espionage charges by a military court was at best misguided and at worst far more sinister than that - a theme incidentally also explored by Italian semiotician and public thinker, Umberto Eco, in his novel The Prague Cemetery. Bringing the travesty of justice in respect of Dreyfus into a nexus of calumny and evil, Eco makes the documents, on the basis of which Dreyfus was handed a life sentence on the notorious Devil's Island, a forgery perpetrated by the same (fictional) character responsible for the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

Though eventually vindicated with the final release and recommissioning as a Major of Dreyfus in the French military in 1906, Zola was appallingly treated by a right-wing French administration shot through with anti-Semitic undercurrents and himself sentenced to a year in prison and a 3000 franc fine for (correctly) identifying the real spy and the central figures in the conspiracy.

There is, in short, some occasion in the narrative for the kind of blood-hot anger captured in the denunciation "J'accuse". But beyond the righteous narrative of a miscarriage of justice, what makes the Dreyfus Affair so significant is that it was happening in what at the time was the epicentre of modernist art and the intellectual avant garde, and, in the public reaction especially to Zola's open letter, ended up profoundly polarising French society into supporters of Zola styled as Dreyfusards - including Claude Monet, Marcel Proust, politician Georges Clemenceau, and the sociologist Emil Durkheim - on one side, and the generally reactionary forces of anti-Dreyfusism and anti-Semitism on the other.

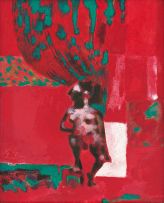

What is on trial then in the Dreyfus Affair - and what transcends the specific narrative on which it is based, is nothing less than western civilisation, and the position of the artist within its social compact. In Hodgins' telescopic treatment, essayed in deliberately - though deceptively - crude figure drawing and an accumulation of brutally quasi-forensic detail, like the swathed or bound figure in the disembodied doorway in the background, and expressionistically traversed and bound together by urgent and restless brush marks dominantly in the register of red, the human is vividly to the point of fixation played off against the cold and ordered impersonality of power and social control. While the narrative is ambiguous and the detail more evocative than historically referential, the passion - a passion that is so linked up with corruption and complicity that it is barely distinguishable from corruption itself and infects the painting surface as a whole - is as palpable as it is inescapable. With its simultaneous evocation of vulnerability and sheer brutality in the claw-like and somehow desiccated gesticulating hand playing off a free arm poking out from a torn sleeve undersized, the painting generates a remarkable sense of urgent desperation and a blackness of soul. And though it is not clear whom or what is the object of Hodgins' accusation, the painting is powerfully pregnant with crisis as the artist looks to a new South Africa from the vantage of what he once described as "the fag end of an arsehole century".

1. Robert Hodgins' Madhouse with View of Tyburn, painted in 1995, was acquired by Iziko South African National Gallery in 1996.