Important South African and International Art, Decorative Arts & Jewellery

Live Auction, 16 October 2017

Evening Sale

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

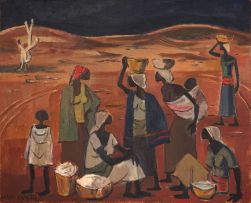

inscribed on the reverse: "My first primitive painting in 1938 after my return from Europe" and "This is the first painting in which I break away from Impressionist art. I think it is in the year 1938. I still continued my orthodox impressionist painting working on primitive art forms until it became a definite part of my style. I called this painting "The Early Men". This work is therefore the first painting by a South African artist using our primitive art as a direct reference. Walter Battiss, 17 Oct 1960"

Notes

In 1933, Walter Battiss discovered what he described as the "bigness of South Africa" when he saw damaged rock paintings on a farm at Malopodraai in the Free State. In a letter to Erich Mayer, Battiss described his intrigue at the "tone values" of these rock paintings, adding that "this area around here requires special study".¹ Over the next two decades Battiss, then still an art master at Pretoria Boys' High School (PBHS), dedicated much of his spare time to finding, documenting and publishing details about rock art across the length and breadth of southern Africa. He became a noted authority on both rock engravings (petroglyphs) and rock paintings, the two distinct forms of rock art found on the subcontinent. Battiss self-published five books on rock art through his Red Fawn Press and wrote articles for books and journals, including The Studio of London (1948) and Lantern (1951).

This important early painting records how a self-directed archaeological enquiry decisively influenced Battiss's career as a painter. In 1938, at age 32, Battiss made his first trip abroad, travelling from London to Paris and Tangier. There are various accounts of this trip and its influence on his practice. Murray Schoonraad, a former PBHS pupil and travel companion of Battiss who later figured as an ardent champion, emphasises his meeting with Henri "Abbé" Breuil, a French Catholic priest and noted expert on European and North African rock art. Battiss also visited prehistoric sites in the south of France, as well as Arles where Vincent van Gogh had lived. Schoonraad links these events to the production of this formative work, made shortly after Battiss returned to South Africa.²

Painter Larry Scully, who taught at PBHS (1951-65) and wrote his Master's thesis on Battiss, offers a fuller analysis of Battiss's 1938 trip. "It was like a visit to the moon," the artist told Scully of his trip.³ Scully accounts for this reaction as follows: "From the comfortable world of a pre-war South African existence [Battiss] was projected into a world of strange and violent forms. Forms which seemed to him a destruction of the human image and of all that he had been lead to believe to be authentic."4 Battiss told Scully that he realised for the first time that "European artists were stealing from Africa the vital forms and colours", which he had previously ignored. "For Battiss this was probably the most important lesson he was to learn: he must open his mind to everything that contemporary European painting had to offer, and he must open his eyes to the autochthonous forms of the whole of Africa".5

Battiss began to experiment with oil painting after his return. The serene figures in this early statement of intent by Battiss recall the prelapsarian world evoked by Cézanne and Matisse in their canonical modernist studies of bathers. However, this painting is fundamentally informed by the techniques of local rock painters, notably their use of elongated forms, and what Battiss in 1945 described as "the serenity and dignity of statement made with the machinery of form".6 This painting describes Battiss's recognition that there was equivalence and correspondence between the two worlds of art that interested him, the one near and ancient, the other geographically far away but closer in time.

1 Murray Schoonraad. (1985) 'Battiss and Prehistoric Rock Art', in Walter Battiss, Karin Skawran and Michael Macnamara (eds.), Cape Town: A.D. Donker. Page 40.

2 Ibid., page 43.

3 Larry Scully, Walter Battiss, Master's thesis, University of Pretoria, March 1963, page 23.

4 Ibid., page 23.

5 Ibid., page 24.

6 Walter Battiss quoted in text panel (WBC/08/01, 1945) at exhibition 'The Origins of Walter Battiss: Another Curious Palimpsest', Origins Centre, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 2016.

Provenance

Prof. Murray Schoonraad and thence by descent.

Exhibited

Shown in the public art museums of the following cities: Pretoria, Johannesburg, Pietermaritzburg, Durban, Port Elizabeth, Cape Town and Kimberley, Walter Battiss: Comprehensive Exhibition, 26 September 1979 to 31 August 1980, catalogue number 2.

Parys en Suid-Afrikaanse Kunstenaars 1850-1965, South African National Gallery, Cape Town, 14 April to 29 May 1988 and Johannesburg Art Gallery, 22 June to 17 July 1988, catalogue number 78.

Pretoria Art Museum, Pretoria, Looking at Our Own: Africa in the Art of Southern Africa, 20 June to 15 August 1990, catalogue number 32.

Literature

Karin Skawran and Michael Macnamara. (eds) (1985) Walter Battiss. Johannesburg: AD Donker. Pages 43 and 151, illustrated on pages 44 and 153.

Lucy Alexander, Emma Bedford, Evelyn Cohen. (1988) Parys en Suid-Afrikaanse Kunstenaars 1850-1965. Cape Town: South African National Gallery. Page 96 and 97 and illustrated on page 93, catalogue number 78.

Karin Skawran. (ed.) (2005) Walter Battiss: Gentle Anarchist, Johannesburg: The Standard Bank Gallery. Pages 21 and 22 and illustrated in colour on page 23.

Warren Siebrits. (2016) Walter Battiss: "I invented myself". Johannesburg: The Ampersand Foundation. Page 26.