Important South African and International Art, Decorative Arts & Jewellery

Live Auction, 16 October 2017

Evening Sale

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

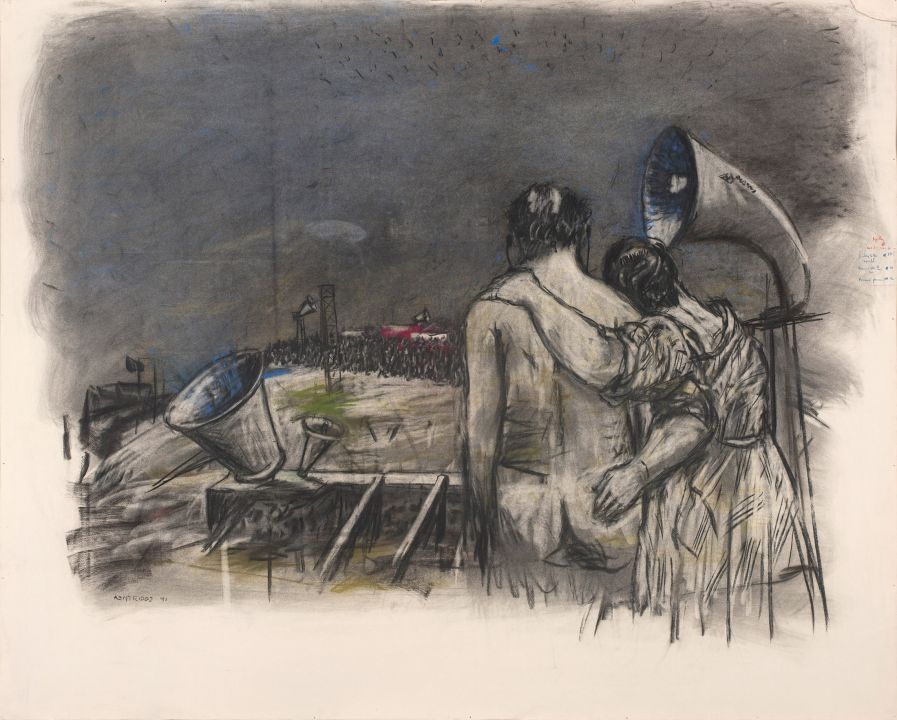

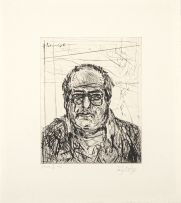

signed and dated 91

Notes

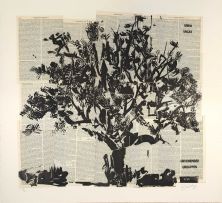

Sobriety, Obesity, & Growing Old is the fourth film in William Kentridge's Drawings for Projection cycle of stop-animation films. The film picks up on the troubled love story introduced by Kentridge in his debut film, Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City after Paris (1989). Soho Eckstein, the overbearing industrialist whose wife has been involved in an illicit affair with whimsical artist-figure Felix Teitlebaum, is faced by financial ruin. It is one of many losses faced by Soho Eckstein. His wife also leaves him, choosing instead her young paramour's "open landscape of megaphones, loudspeakers and passion".¹ This drawing, one of 25 Kentridge progressively altered through erasure and redrawing during the production of the film, dramatizes this pivotal moment.

As in his first film, indicators and signs of social upheaval are interjected into the action of film, complicating a discrete love story involving archetypal white characters. The film is shadowed by this immanent reality, although draws to a climax with Felix and Mrs Eckstein making love in the architectural ruins of Johannesburg. Soho Eckstein, ruined, alone and possibly repentant, contemplates an open landscape with a cat. "Her absence filled the world", a textual caption reads.

The film won Kentridge the gold medal at the last Cape Town Triennial in 1991, where it also premièred. The film has since been widely exhibited. In 2001, Kentridge was the subject of a major survey exhibition at New York's New Museum of Contemporary Art. Arthur C Danto, an influential American art critic and philosopher, reviewed the exhibition for The Nation. His review included a detailed appraisal of Sobriety, Obesity, & Growing Old (1991), in particular the film's description of events at the edge of South African political history.

I am very impressed by the way, as an artist, Kentridge seeks to reflect political problems through interpersonal relationships … At the edge of huge social upheavals, yet also removed from them. Not able to be part of these upheavals, nor to work as if they did not exist. That is the way I see his art - not part of the upheavals but to be understood through the fact that they exist and in some deflected way explain the art. In the end, if one thinks about it, this is the way artists have often dealt with political upheavals: at their edge, and in the framework of love stories. Think of Hemingway or Tolstoy or, if you like, Jane Austen or possibly Matisse.²

1 Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev. (1998) William Kentridge, Brussels: Société des Expositions du Palais des Beaux-Arts. Page 74.

2 Arthur C. Danto. (2001) 'Drawing for Projection', The Nation (USA), 28 June.