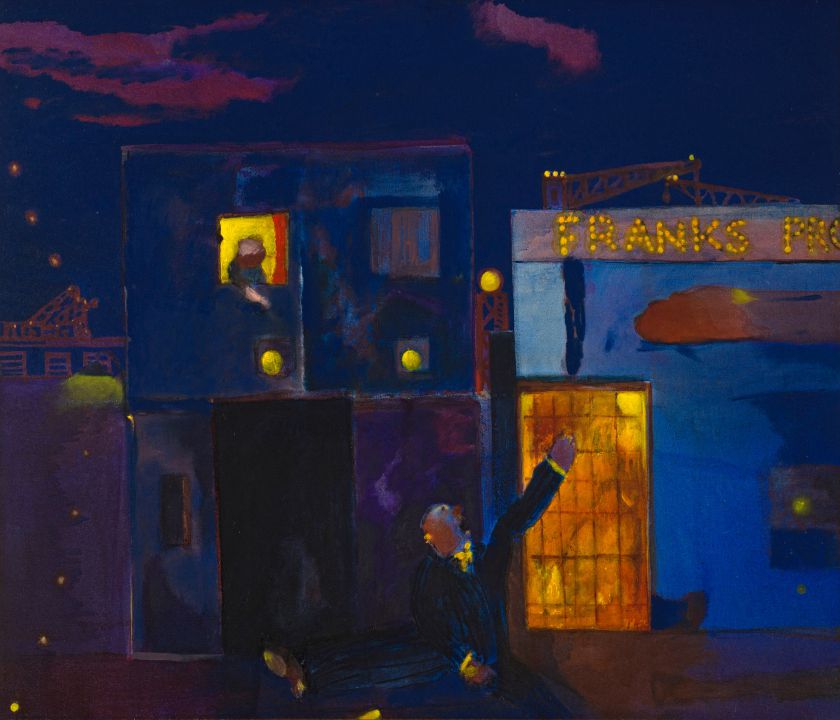

Drunk in the Docks

Robert Hodgins

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

signed, dated 1996/7 and inscribed with the title and medium on the reverse

Notes

"One dressed respectably, old boy, you know, in a pinstriped suit, because that helped you get away with drinking longer into

the night!"

One of the most fascinating ''beads'' in the "string" of Robert Hodgins's life, as told by himself1, is his account of how he came to South Africa following a difficult, if not traumatic childhood in London. Working on a counter in a shop named Libraire Populaire in Dean Street, Soho, Hodgins became aware of the rich cultural life flourishing in that seedy part of town during the 1930s, eyeing, if not encountering, such artists and writers as Dylan Thomas, Francis Bacon, WH Auden and Christopher Isherwood virtually every day. In his early teens, he also delivered newspapers and magazines around Soho for the shop - including the mildly erotic La Vie Parisienne - to titled gentlemen and restaurant owners, Mayfair whores, and nightclub owners alike. He was intrigued by the underbelly of the city. When he eventually got out of Soho, having been given a job in an office to answer the telephone (without ever having seen or used one himself), by sheer chance he met his great-uncle from South Africa, his grandmother's brother. Within fifteen minutes Uncle Billy convinced Hodgins to come out to South Africa. He generously sent Hodgins £33 to buy two pairs of shoes, a suit and a passage on the Edinburgh Castle to Cape Town. Hodgins landed on the docks on his eighteenth birthday with exactly sixpence in his pocket.

Another exquisite ''bead'' in his string of anecdotes tells what Hodgins did on his arrival: '' I started work as an insurance clerk, earning six pounds a month. Uncle Billy made me do matric in the evenings. The great thing was that he owned The Harbour Café, now rather chic on Cape Town's Waterfront. It wasn't chic then - it catered to sailors, dockers, tug-boat crews, that kind of thing. But the glamour - for a London slum boy, you can imagine. The family lived above the café. My passion for art was still secret, although Uncle Billy liked the fact that I read Shakespeare. But when I went to a concert on Thursday night at the City Hall, it was assumed I'd gone to watch all-in wrestling. And nobody was interested in the National Gallery. This went on for over two years. Although war broke out fifteen months after I arrived, Uncle Billy said ''matric first'', and so I joined up only in December 1940''.

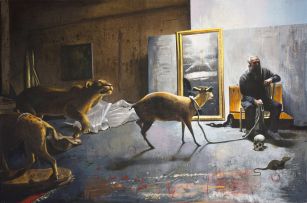

The present lot, Drunk on the Docks, Hodgins described in conversation as being semi-autobiographical. The painting captures Hodgins' youthful excitement at his new environment on the harbour front. Giant cranes visible to the left and the right in the background, frame the scene in the foreground: in a deserted part of the dockland, it is late at night. The sky is rendered in dark blues and purples at one end of this motley collection of buildings, giving way to light blues and mauves on the other, suggesting daybreak in the east. "Of course, after midnight demands lapis blue!" as Hodgins would say.

The central figure, clearly quite inebriated, sits with legs wide apart, waving an arm in the air (incidentally creating a very dramatic diagonal in the otherwise straightforward vertical and horizontal grid of the composition). The artist once shrugged and in a confessional tone admitted that this was the story of himself on a number of nights, exploring the nightlife around the docks.

Referring to the figure as "arguably myself" he said of this canvas, "he may have been raucously singing bawdy songs, or bellowing an obscenity in a drunken ramble after being ejected from a bar. One dressed respectably, old boy, you know, in a pinstriped suit, because that helped you get away with drinking longer into the night!" He enjoyed wearing a yellow, (if not sparkling) bowtie with his prized blue suit.

His sole audience seems to be the woman leaning out of a window above him, a stand-alone portrait of an interested party, if you like. She could well be making an equally wild noise, perhaps even admonishing our drunk, judging from her waving arm, and pointing at our man on the pavement. Or she could be luring him into her room for some pleasures of the flesh. She could well be ''the upstairs Puffmutter'', or brothel keeper at the window. One might even detect a wry smile on her face, looking imaginatively at the small blobs of paint that constitute her face. Frank's, (the name spelled out in flashing light bulbs), the place next door (perhaps a golden opportunity to enter, as suggested by the glowing door!), is metaphorically aflame with the night's carousing. It is dawn! No misery and threat for Robert: he is more interested in the joys of life.

Hodgins presents a memorable glimpse of a young man newly earning and able to enjoy with gusto the liberated pleasures of a different life, far from the hardships of cold, wet London, no matter how humble. He uses the device of lights glittering in a darkness which is gradually lifting, to great effect, to express the memory, in hindsight, of being on the brink of greater possibilities.

- Neil Dundas, 2018

1. Robert Hodgins. (2002) A String of Beads: An interview with Robert Hodgins by Robert Hodgins. In: Brenda Atkinson 2002 Robert Hodgins. Cape Town: Tafelberg Publishers. Pages 20 to 31.

Literature

Brenda Atkinson et al. (2002) Robert Hodgins, Cape Town: Tafelberg. Illustrated in colour on page 25, with the title Drunk on the Docks.