Modern, Post-War and Contemporary Art

Live Auction, 20 May 2019

Evening Sale

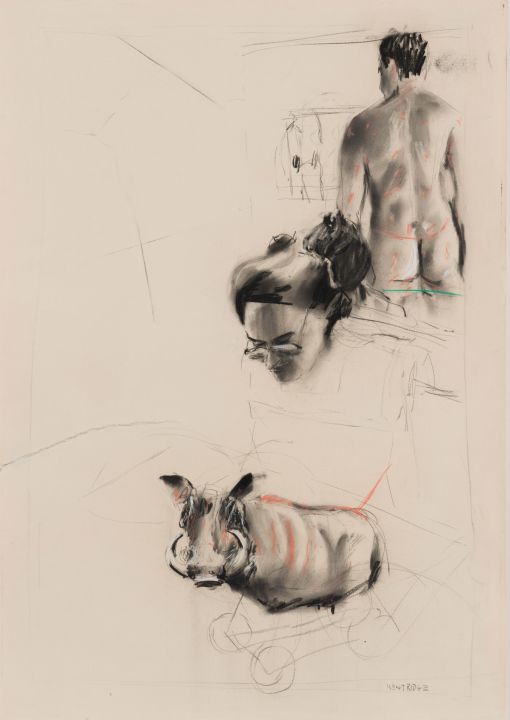

About this Item

signed

Notes

'I certainly think drawing is the closest way we have of making visible the way we are in the world, both the way we think and the way we move through the world, which is provisional, changing, constructed out of incoherent fragments into a seemingly coherent subjectivity. And I think that drawing, and the process of making a drawing is as good a method as any for that activity.'1

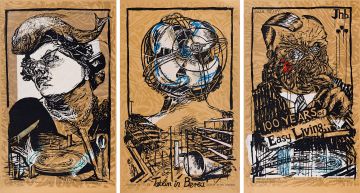

What seem to be three loose, fragmented motifs (a warthog, the face of a woman, and the back of a nude man) in a drawing by William Kentridge, are in fact three quite significant images in his oeuvre. The drawing was made in the mid-1980s when Kentridge was exploring visual metaphors for a country under siege. The situation reminded him of the crumbling interwar Germany of the 1920s and early 1930s and the art produced by such second-generation German Expressionists as Georg Grosz and Max Beckmann. Kentridge set his sights on the complacent middle classes in South Africa, producing such ironic works as the triptych, The Conservationist's Ball (Culling, Game Watching, Taming) (1985), which has trinkets of Africa embellishing the picture plane, including a miniature rhinoceros dancing on a table, a civet pelt draped around a shoulder, and a warthog floating over diners in a café.

The image of a warthog appears again in a work, titled Family Portrait (1985), a work referring to three generations of Kentridges: his grandmother in the far background, his parents in the middle ground, and the artist and his wife, Anne, in the foreground. This time the shirt of the artist is printed with small green rhinos.

The motif of the back of a nude man, first appearing in a work titled Flood at the Opera (1986), recurs often in Kentridge's subsequent works, such as in the drawings for the video piece, Johannesburg, Second Greatest City after Paris (1989) which has a memorable frame of the same nude, this time possibly an alter ego, the artist Felix Teitlebaum, foil to the capitalist, Soho Eckstein, staring at a drive-in screen bearing the words 'Captive of the City'. And again later, in a series of prints collectively referred to as Man with a Megaphone (1999). The three arbitrary images in the present Lot take on the function of a repository of meaning with personally relevant references.

1. William Kentridge, quoted in Leora Maltz-Leca (2018) William Kentridge: Process as Metaphor and other Doubtful Enterprises, Oakland: University of California Press, page 195.