Modern, Post-War and Contemporary Art, Decorative Arts, Jewellery and Wine

Online-Only Auction, 15 - 22 February 2021

Paintings

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

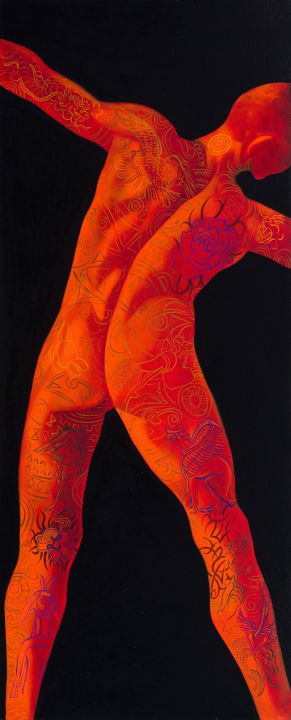

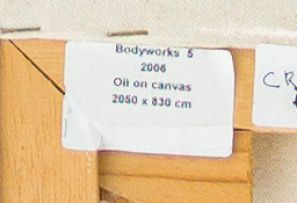

dated 2006 and inscribed with the title and the medium on a label adhered to the reverse

Notes

'Andrew taught me so many things over the decades of our friendship and these are a few of them.

I don't think I know anyone possessed of more enthusiasm than Andrew, for art, for literature, for food, for music, for fabric and pattern and colour and for friendship. But perhaps his most bountiful capacity was an enthusiasm for other people's work. He was the most generous viewer.

His curiosity and sheer excitement about the work of young artists was so invigorating. To witness this erudite, extraordinarily accomplished artist and writer engaged by your work was to see its value yourself.

He taught by making us recognise the particularity of our own interests, and then to find a vocabulary for that interest. He would always be on hand with suggestions and references to other artists, movements and ideas, because … as he knew well, we all need kinship.

He had enormous enthusiasm for place, for Durban, as a climatic envelope, as a collection of fluid ideas about history, and as a present-tense challenge. When I lived there my own view of Durban was enlivened by Andrew's eye and I have used the lesson wherever I have stayed. But Andrew made me powerfully aware that his depictions of beaches and beach boys, of pennants fluttering on a pole against a darkening sky or deck chairs stacked against the wind are but the conduit to something else, ideas as yet un-worded. The idea of art as a conduit to the un-namable, was a lesson in how we can make art of anything, the ordinary, the quotidian and the forbidden - that things can be themselves and yet be other.

Andrew made me think on and value beauty as both a skill and an act of will. Beauty in how one tone lies against another, the beauty of a line transitioning from jaw to neck or the beauty of light behind clouds busily opening to the wind. His lines of beauty are an assertion of curiosity and attentiveness, an assertion of the lyrical, the ambiguous and the speculative rather than the known, but most importantly for me an assertion of empathy - with looking as the bridge.

Empathy asserted against the known codes of association is a political act and Andrew was always a political being. His attentive, eroticised gaze on the male body was revolutionary at the time. It is easy to forget just how pervasively toxic masculinity affected all aspects of our behaviour in this country. Redirecting our gaze was liberating to me as a young, repressed man whose psyche had been constructed, alas, within that toxic mould.

Deconstruction was the subtext of much of Andrew's teaching.

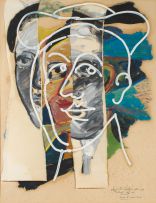

I remember him encouraging me to scribble. This was a shock to the earnest young man that I was. I had studiously learnt the skills of drawing and I took pride in doing it well. His point was that any reasonably intelligent and logical person could look at a subject and assemble its constituents in the right order, but it is in breaking the rules that we understand the true value and capacity of language.

I don't know how many exhibitions Andrew had in his career, but it is scores. I have this image of him always in the studio, making and making and again fervently making - and then at the end of daylight going in to Aidan, who was always ready with a beer in a large quart bottle.

When he wasn't in his studio he was at the typewriter, writing reviews, recording his delights … and his outrages. When I was in Paris for six months there was seldom a day that went by without a letter from Andrew. It could be pages or simply a note about something he had seen, a piece of local gossip or something he remembered. I looked forward to those notes and often he, who had been in Paris before me, asked if I had yet been to a bar, cruised a park or seen a work he loved in a dark and neglected corridor of the Louvre.

But his most abiding lesson for me was in the assertion of friendship and community. He referred to a group of younger artists who loved him as 'the family' and that was a role I treasured.'

Clive van den Berg