Modern, Post-War and Contemporary Art, Decorative Arts, Jewellery and Wine

Online-Only Auction, 15 - 22 February 2021

Staff Picks

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

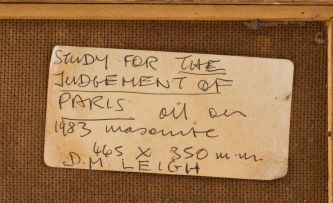

signed; dated 1983 and inscribed with the title and the medium on a label adhered to the reverse; a letter from the artist to 'Dear Gitte' in an envelope adhered to the reverse

Notes

This item was picked as a Staff Pick by Alastair Meredith, Senior Art Specialist, HOD, from the Johannesburg office.

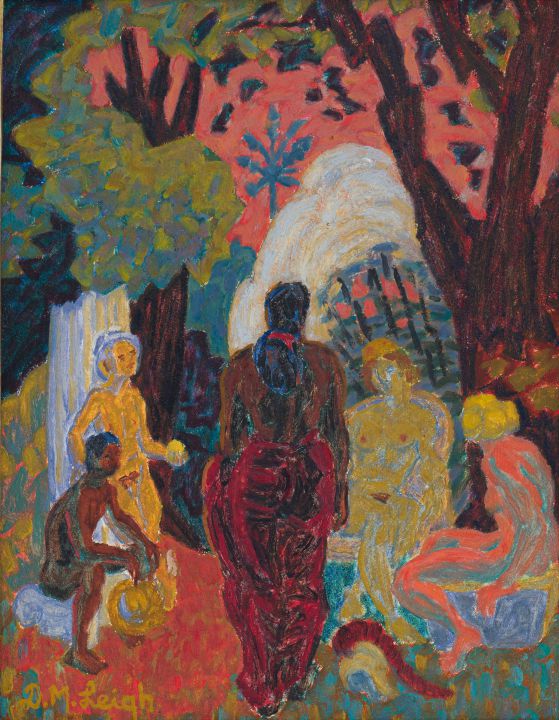

Derek Leigh's Study for the Judgement of Paris references the ancient Greek myth in which Paris, the son of the Trojan King Priam, is asked to judge between the Greek goddesses Hera, Athena and Aphrodite and award the golden apple to 'the fairest of all'. This is a recurring subject in Leigh's work: a watercolour of the same subject forms part of the Tatham Art Gallery collection in Pietermaritzburg and a number of other works in various media were exhibited as part of the artist's memorial exhibition at the gallery in 1995, including a final version of this study.

Leigh could be considered part of the 'School of Paris', a term applied loosely to the many non-French artists, including a surprising number of South Africans, who studied and worked in Paris in the early- to mid-twentieth century. In France, Leigh would have been very aware of the work of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, and his rich, vibrant colours, stylised figures, and bold painterly brush strokes suggest a particular interest in the work of the Nabis, a group of Post-Impressionist artists who were partly influenced by Paul Gauguin. In particular, Leigh's use of mustard for one of the goddesses and the figure holding out the golden apple recalls Gauguin's unnatural colour palette in his painting The Yellow Christ (1889, now in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in New York). Leigh elicits an emotional response from the viewer through the use of evocative artificial colour and animated dappled paint application, characteristics also found in the work of Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, pioneers of the Nabis.

The artist's use of an impressionistic style to depict a mythological subject matter is ironic as one of the main motivations of Impressionism was a revolt against the conventional, staid subjects that dominated academic painting in France in the mid-nineteenth century: history painting, religious subjects, and mythological scenes.

Despite the depiction of a theme centred on the beauty of the human body, Leigh's semi-abstract depiction of the figures opposes the idealised realism that reached its first peak in Western art in the Hellenistic period (roughly 323 BCE to 31 BCE). Compositional similarities make it clear that Leigh was aware of Baroque artist Paul Rubens's famous utopian representation of The Judgment of Paris, (c. 1636, now in the National Gallery, London),1 which is set outdoors in a romanticised classical landscape even though, in the original telling of the tale, the event took place at a banquet, indoors one would imagine. The use of exaggerated brushstrokes, unnatural colour and a lack of spatial depth continues the artist's rejection of idealistic realism and appears to almost parody the work by Rubens.

The contours of the five figures create organic lines that lead the viewer's eye swiftly through the composition. These curved lines contrast with the tall, rigid branches that reach into a vivid red sky and appear to spread out beyond the painted surface. The arbitrary use of colour - orange grass, mustard bodies and light blue shadows - creates a mystical atmosphere that is further enhanced by the illusion of spatial depth and balance, created by colour rather than any conventional system of perspective, especially the complementary blues and greens in the background.

Like Rubens, Leigh places a partially draped nude female figure with her back to the viewer at the centre of the composition. Her importance is accentuated by her tall upright stature and the gazes of the surrounding figures being directed towards her, making her the focal point of the work. In contrast to Rubens's fleshy white goddess, however, Leigh's appears to be a black woman. "It's a Judgement of Paris set with South African figures, I suppose," the artist explained of the final version of the work, an "Indian woman, a black Paris, a black boy, a red sky to suggest the violence that's going to come out of this decision, which resulted of course in the Trojan War, and smoke, broken branches suggesting spears. I tried to make the shapes, the jagged, broken shapes suggest the potential for violence in this apparently pastoral scene,"2 and no doubt, Leigh seems to argue in this work, in South Africa as well.

Although painted in 1983, this work is even more relevant today because it also highlights the socio-political issues of beauty and aesthetics, as beauty pageants are currently under scrutiny for objectifying women and subjecting them to unrealistic beauty standards. Leigh's Study of the Judgement of Paris attempts to question gender politics and the male gaze - unlike in Rubens's work, here the two male figures are also nude - and redefine aesthetics through parody in an almost post-modernist rejection of realism and art historical precedent.

Yasmien Mackay

1. Other examples in the series of Leigh's works on this subject reproduce Rubens's composition more closely than the present lot, in the poses of the goddesses particularly, confirming that he was familiar with the older work.

2. Brendan Bell and Bryony Clark (1994) Derek Milton Leigh, 1940-1993: A Memorial Exhibition, catalogue, page 47.