Important South African and International Art

Live Auction, 5 June 2017

Evening Sale

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

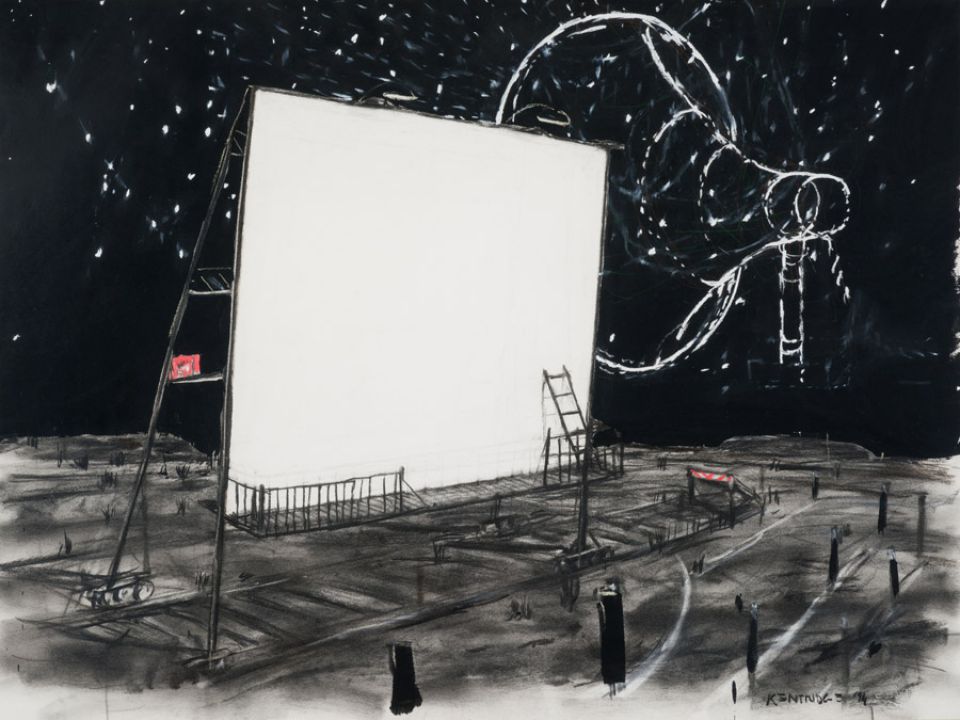

signed and dated 94

Notes

In 1994 William Kentridge directed the music video for Another Country ( watch the video), the title song from popular musical ensemble Mango Groove's third album. (For a full discussion of the collaboration, see Lot 259). This drawing appears two and half minutes into the music video and features vocalist Claire Johnston 'projected' into the blank area of the drive-in screen. She sings: 'There is a place for anger, things we won't forgive/ And I know it's not enough to face your shame with words you'll never live.'

The megaphone and drive-in screen are common motifs in the artist's work. Kentridge's recent film Other Faces (2011), for example, includes studies of Top Star, a drive-in cinema that sat atop a mine dump in central Johannesburg. The megaphone first appeared in his animated film Monument (1990). In a 1999 interview with art historian and curator Carolyn Christov-Barkargiev, Kentridge explained that megaphones 'indicate what needs to be heard or seen, outside of oneself. I draw megaphones because... they appear, for example, in photographs of Italian Futurist concertos for factory workers. I feel I'm part of earlier heroic attempts at connecting the world with art'.1 It is not an illogical jump from concertos for factory workers to music videos for mass audiences.

Kentridge's treatment of the night sky also deserves comment. It clearly shows evidence of Kentridge's iterative method of drawing, of creating a drawing that is 'continually making itself - marking, erasing, and eventually changing into different images', to quote the artist.2 In Kentridge's music video, the space occupied by the megaphone initially features a tin of fish, which morphs into the megaphone, a process that also generated a constellation of quasi-stars.

In 1998, during the first blush of international success, Kentridge exhibited his work at The Drawing Center in New York. He was explained as 'the Anselm Kiefer of South Africa' by one critic.3 The comparison was no doubt influenced by Kiefer's and Kentridge's toned-down palette and sombre examinations of German and South African history. The art historian Gerhard Schoeman further explored their affinities, writing at length about Kiefer's and Kentridge's 'melancholy imaging of history as catastrophe'.4 According to Schoeman, Kentridge and Kiefer shared a similar way of working: of repeatedly returning to the 'haunted/haunting site' of the past as 'a sombre point from which to project the irreducible complexities of the present'.5 Another Country, a melancholic ballad steeped in the dilemmas of history, is similarly constructed: the peace song was consciously written with the 1992 Boipatong massacre and 1993 assassination of South African Communist Party leader Chris Hani in mind. Kentridge's suitability or rightness to direct the music video is clear.

1 Judith B. Hecker, William Kentridge: Trace - Prints from The Museum of Modern Art, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010, page 60.

2 Michael Auping, 'Double Lines, A "Stereo" Interview about Drawing with William Kentridge', in William Kentridge Five Themes, San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2009, page 241.

3 Roberta Smith 'William Kentridge', New York Times, 6 February 1998, page E36.

4 Gerhard Schoeman, Melancholy Constellations: Walter Benjamin, Anselm Kiefer, William Kentridge and the Imaging of History as Catastrophe, unpublished doctoral thesis, University of the Free State, May 2007, page 131.

5 Ibid., page 118.