Important South African and International Art

Live Auction, 5 June 2017

Evening Sale

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

signed and dated '94

Notes

In 1994 William Kentridge directed a music video for the popular musical ensemble Mango Groove. Formed in 1984 by bassist and songwriter John Leyden and fronted by vocalist Claire Johnston, Mango Groove is known for its 'marabi pop' sound, a fusion of kwela and marabi big-band jazz traditions with western pop. The mixed-race band came to prominence with their song Special Star, included on its eponymous 1989 debut album.

In 1993 Mango Groove released Another Country ( watch the video), an ambitious crossover album featuring a stellar line-up of guest musicians, including guitarist Condry Ziqubu, jazz bassist Sipho Gumede and ethnomusicologist Andrew Tracey. The album was well received by critics. Billboard, a respected industry magazine in the United States, praised the album's title song as 'one of the most beautiful songs to emerge from the transition to democracy'.1 Kentridge's music video is low on concessions to the pop music genre and was produced in the style of his stop-motion films. It however differs from his career-defining films by featuring a live actor, Johnston - she is the only member of the band to appear in the video. Set in an abstracted version of Kentridge's Johannesburg, the music video includes ample evidence of social tumult. The heaving throngs with red banners, who march down city streets and congregate around pylons and monuments, are clearly referenced from Kentridge's earlier films Monument (1990) and Sobriety, Obesity, and Growing Old (1991).

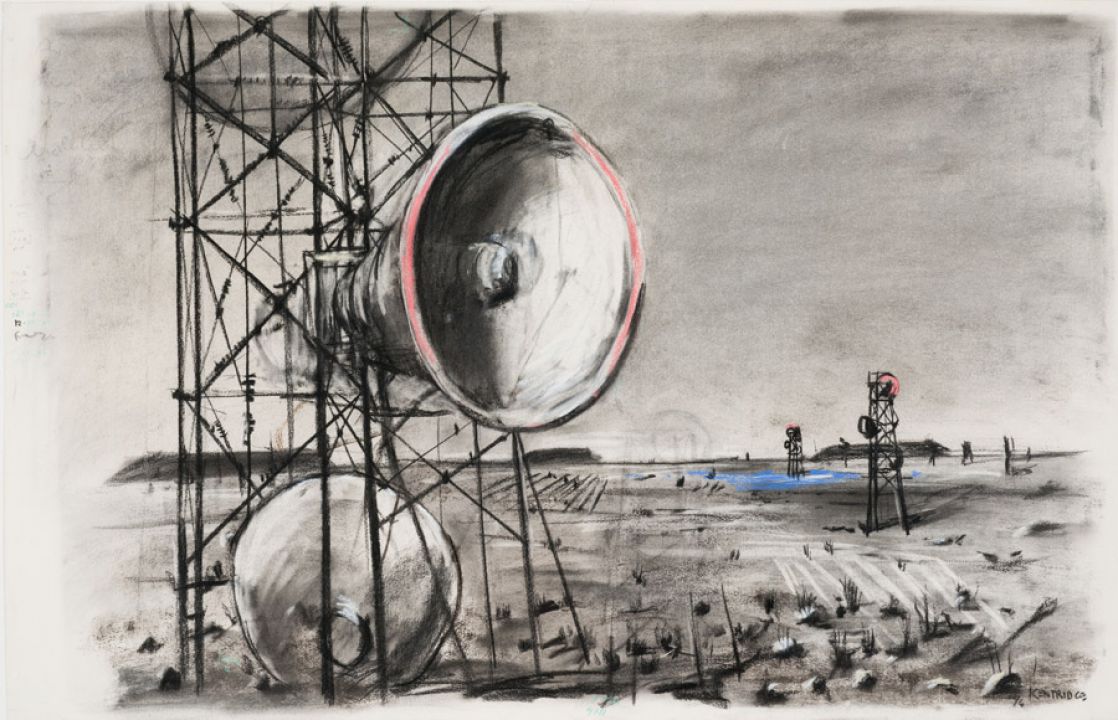

Similar to his theatre collaborations with the Handspring Puppet Company, in which live actors and puppets interact with the artist's projected drawings, Johnston's performance revolves around her negotiation of this scenography. Johnston is presented as a larger than life presence in Kentridge's charcoal-drawn world: she is at once an entertainer, whose image fills billboards and drive-in screens, and a rainmaker able to bring relief to a complicated and visceral reality. This particular drawing forms part of the music video's opening montage, which culminates in Johnston's introduction. Pylons and megaphones feature prominently in Kentridge's work from the 1990s. The earliest examples appear in his etching series Little Morals (1991), as well as the two films already mentioned. The pylons reference the form of the tower-like structures that carry electricity cables across Johannesburg, as well as the steel headframes of the city's defunct gold mines. But their function in the music video is specific, and connected to ideas of mass communication and propaganda that occupied Kentridge at the time.

During a lecture at the National Arts Festival in 1986, Kentridge spoke of his interest in Soviet painter and architect Vladimir Tatlin's Monument to the Third International (1919-20). Ambitiously scaled and purposefully propagandist, Tatlin's Bolshevik-sponsored monument to the glory of the Russian revolution was also famously unrealised. Kentridge referred to Tatlin's speculative architectural piece as 'one of the great images of hope… a hope and certainty that I can only envy. Such hope, particularly here and now, seems impossible'.2 This idea of deferred hope amidst insurmountable odds is a key theme of Mango Groove's song. Another Country was written with two recent events in mind: the 1992 Boipatong massacre and 1993 assassination of South African Communist Party leader Chris Hani. The song's lyrics speak of 'a place for anger' and actions that are hard to 'forgive', but also poses a counter argument: 'let's begin to look within, to where the future lies/ And find the strength to live beneath another country's skies/ Another time, another place/ Another country, another state of grace'.

Kentridge was also interested in this notion of achieving a state of grace. In his 1986 lecture he spoke at length about the complexities of making art in a country where 'one's nose is rubbed in compromise every day'.3 Kentridge's understanding of the ethical complexities of achieving a state of grace in a situation where he was 'neither active participant nor disinterested observer' may account for his ambivalence towards the finished music video.4

Kentridge's music video was well received at the time of its release, winning a prestigious Loerie award in 1994. Now, two decades later, this drawing from that video is a valuable document of creative collaboration from a fraught political time. It shows Kentridge, then still little known outside art and theatre circles, successfully testing his ideas in the mass-market pop realm.

1 Arthur Goldstuck, 'South African artists reflect optimism', in Billboard, 30 April 1994, page 89.

2 William Kentridge, 'Art in a state of grace, art in a state of hope, art in a state of siege', in Carolyn Chistov-Bakargiev (ed.), William Kentridge, Brussels: Société des expositions du Palais des beaux-arts de Bruxelles, 1998, page 56.

3 Ibid.

4 Stella Viljoen, 'Authorship and auteurism in Another Country', Tydskrif vir Letterkunde, 2004, Vol. 41 (2), page 53.