Important South African and International Art, Decorative Arts & Jewellery

Live Auction, 5 March 2018

Art: Evening Sale

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

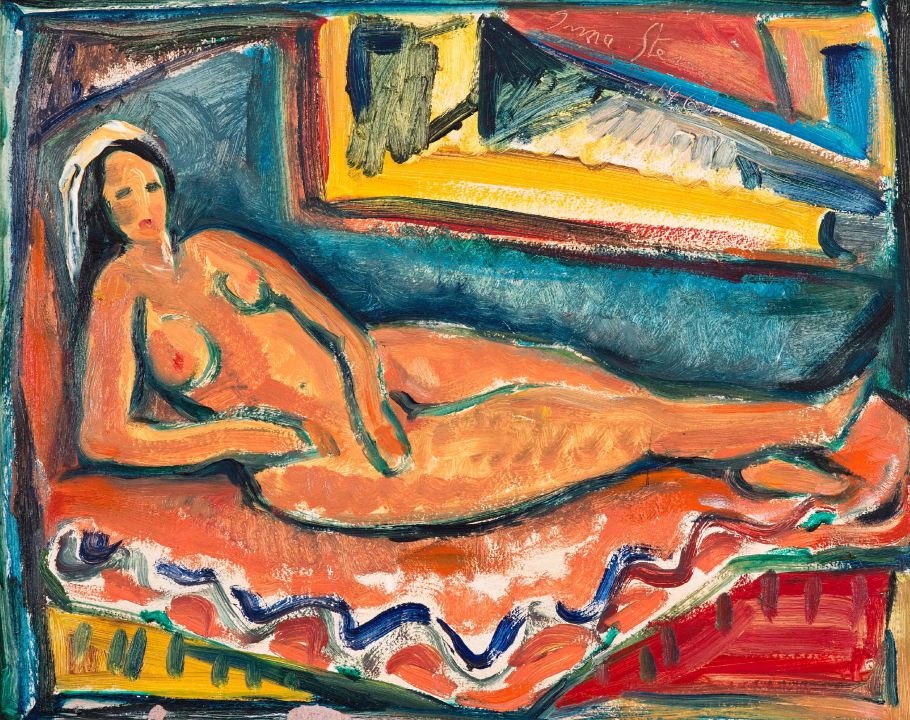

signed and dated 1962

Notes

"My appearance is that of a well-dressed lady, but inwardly I run more and more wild" - Irma Stern to Trude Bosse1

The female nude is well represented in Stern's oeuvre, appearing in various guises across the range of media in which she worked. From vigorous ink drawings and studies, to figures on glazed earthenware, to prints, gouaches and oil paintings spanning her long and prolific career, the subject was never far from her creative consciousness. This is partly a consequence of the broader artistic context in which she trained and worked, where mastery of the human form was the cornerstone of any serious artist's technical vocabulary. For Stern, however, it appears that the human figure, with all its charged associations of vigour and immanence, was always more than an exercise in form. Rather, it was at the very core of her creative drive, infusing her work with the passion, sensuality, and beauty for which she has become justly celebrated. In recalling her first experience of drawing live models at the Großherzoglich-Sächsiche Hochschule für Bildende Kunst in Weimar where she studied in the early twentieth century, she told the Cape Argus in 1926 that,

"From the very first moment I took the greatest delight in this work. The human body appeared to me to be an instrument for expressing the emotions of the soul. What sorrow lay in a bowed head, in a curved back; what joy and force in a figure standing upright! This was new land and I set out to conquer it with keenest intensity."2

In 'conquering this new land' Stern inserted herself into a long tradition of the nude in Western painting, and brought to the complex ideals, philosophical interests, and cultural references underpinning it a bold vision of an African-inspired expressive modernism. Following her mentor Max Pechstein, her early expressionist vision was rooted in the belief of the primacy of nature over culture, and she devoted a considerable part of her adult life to the pursuit and celebration of what she perceived as the 'exotic' and the 'primitive'. In this context, her nudes come to embody all the sensuality, voluptuousness and fecundity that characterises her entire oeuvre, abundantly evident in the still lifes and landscapes, and never far from the portraits.

These attributes are particularly evident in Stern's numerous paintings of nude Africans, whether singly or in groups. With few exceptions these figures are female, and are strongly reminiscent of Gill Perry's observation, in relation to the figure paintings of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, that they grew out of a "system of Eurocentric values through which both black people and nude women came to symbolize some fantasy of free 'primitive' expression".3 For Stern, it seems that the nude, black female was as much a trope for the purity of unspoilt nature as it was of the power of feminine sexuality.

In the western tradition, the female nude came to embody both the divinity of procreation and the lure of the sensual. The reclining nudes of the Renaissance, depicting Venus recumbent in a landscape or domestic interior, exemplify the latter, highlighting "the seductive warmth of the female body rather than its ideal geometry".4 The development of a new visual language to engage with the new conditions of industrialised modernity in the late nineteenth century, however, had its most powerful impact in the radical revision and subversion of traditional subjects, not least the female nude.

Édouard Manet's Olympia (1865) is a key example in this regard. Olympia clearly references Titian's reclining Venus of Urbino (1534), but subverts its tropes of languid, unthreatening sensuality by presenting a noticeably modern subject in an aggressively modern style. Where Titian's Venus, demure and serene, possesses all the trappings of the ideals of femininity of her time, Manet's Olympia was immediately recognizable to a contemporary audience as a working-class prostitute, trading her flesh like any other commodity in the gaslit world of the Parisian demi-monde. The painting's broad, quick brushstrokes, shallow depth and lack of mid-tones overturned all academic conventions and drew attention to the expressive potential of modernist technique, insisting on a shift from the perceptual to the conceptual as being the necessary condition of modern art. Increasingly, as traditional Western values of sensuality and beauty were no longer seen to be equal to the task of expressing modernity, European artists also began looking to Asia and Africa for a new language of form, and these technical disruptions became infused with an interest in the exotic and 'primitive'

Although produced late in her career, Stern's Reclining Nude is quintessentially at this intersection: while the reference to Olympia is difficult to ignore, the painting's spirited colour, vigorous brushstrokes, and unabashed exoticism of the figure's caramel-coloured skin, boldly outlined in green, and her pitch-black hair cascading from a headscarf, recall the many female nudes in her own repertoire. In effect, the painting is at once a powerful reassertion of her lifelong commitment to the inspiration of the early masters of modernism, while at the same time a celebration of 'primitive' female sexuality, complicated and intensified by the 'wild, inward' force of her own femininity.

Federico Freschi

1. Helene Smuts. (2007) At Home with Irma Stern: A Guidebook to the Irma Stern Museum, Cape Town: Irma Stern Museum. Page 16.

2. Paul Cullen. (ed.) (2003) Irma Stern: Expressions of a Journey, Johannesburg: Standard Bank Gallery. Page 98.

3. Gill Perry. (1999) Gender and Art, New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Page 7.

4. Jean Sorabella. (2008), "The Nude in Western Art and Its Beginnings in Antiquity." In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/nuan/hd_nuan.htm (Accessed 5 February 2018).