Important South African & International Art, Decorative Arts & Jewellery

Live Auction, 6 March 2017

Important South African and International Art - Evening Sale

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

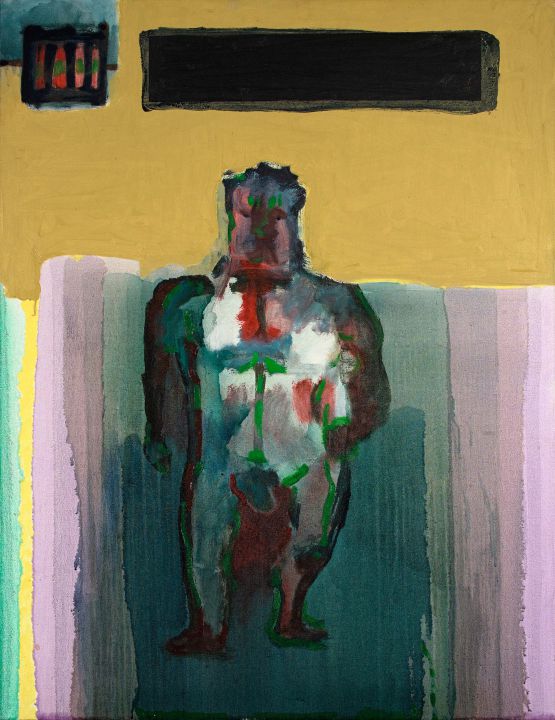

signed, dated 2006 and inscribed with the title and medium on the reverse

Notes

The Goodman Gallery label adhered to the reverse.

Leonardo da Vinci famously advised artists looking for inspiration to contemplate stained walls or mossed stones. There, Leonardo said, they would find no end of suggestion: from landscapes to trees, to battle scenes, to the "lively postures of strange figures", not to mention the ranges of facial expression by which emotion is conveyed.

To an extent Robert Hodgins' work engages with the same sense of artistic creation - but in reverse. The painting is constructed around the radically simplified figure of a naked man; a figure drawn in such way as to eschew the happenstance and detail of individual appearance. Instead what is highlighted is a distinctively modernist concern with other, less literal, levels of presence, materiality and painterly value. What concerns the artist is not so much how things look as how they feel.

To this end, Hodgins develops an all but codified system of formal dysfunction: limbs that don't quite match; a face that dissipates rather than resolving into features or expression; eyes that are the merest dots and lack all gaze; a discoloured hanging scrotum, the implied violence displaced to a dirty red ground between the legs; tiny useless fists.

A man without heft or qualities, much reduced by the condition in which he finds himself, less an agent than a repository for what has happened or been done to him. The red at the chest and in the midriff; the green brushstrokes; the shadings discoloured like bruises or contusions.

The subject of Naked in Solitary is, of course, one that had and has particular relevance for South Africans who lived through the militarism that characterised apartheid. But, largely because Hodgins' painterly usages engage the viewer initially at visceral levels, it reads inexorably as a metaphor at the same time - as speaking to some profoundly sombre conditions of the spirit.

This comes through in part in the layering of planes of mainly melancholy colour and tint in the space behind the prisoner figure - foiled though they might be by a chirpy yellow bleeding into blue and green pastels at the left.

But it is over the prisoner's head that there hangs the most telling and the most chilling detail of all. A slot of window to the outside world. It is unrelievedly black. No images for liberating the imagination.

Ivor Powell