Important South African and International Art

Live Auction, 7 November 2016

Evening Sale

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

signed

Notes

'To date, no single event has had a more profound influence on the art of Walter Battiss than his encounter with primitive art.'1

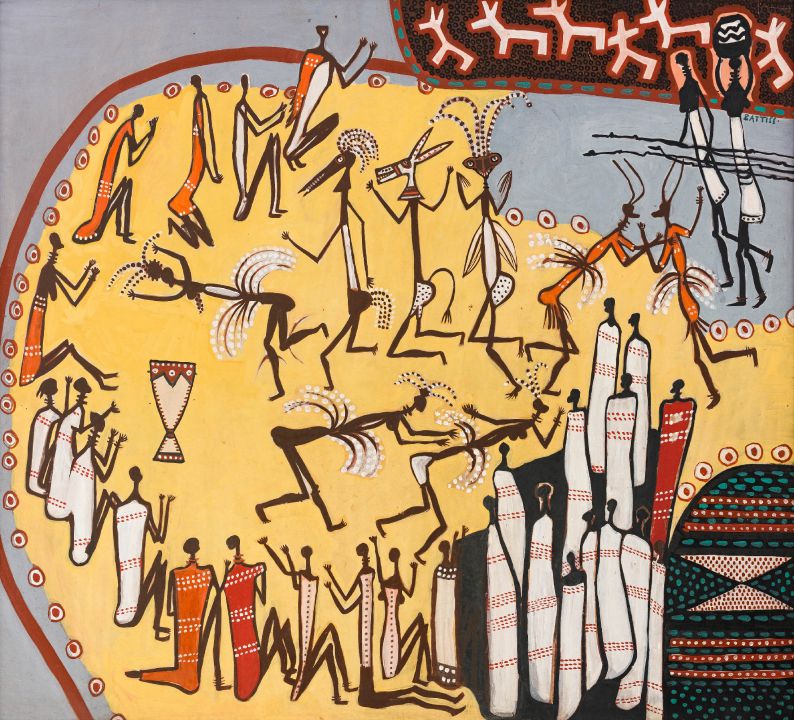

While traces of Battiss's obsession with rock art are easy found throughout his huge and wildly-variant oeuvre, these two large works, repatriated from Sydney, Australia, are rare examples of the artist engaging so directly with rock art in a major composition. These works were originally a single panel, and were later split in two under Battiss's supervision (one panel was re-signed too). Despite the amendment, they remain some of the largest Battiss works to appear on the market for some time.

Battiss was a worldwide authority on rock art, and published seven books on the subject, including Artists of the Rocks (1948), a copy of which he gave to Picasso via his art dealer Henri Kahnweiler on his second trip to Europe in 1949. Picasso subsequently invited Battiss to his studio and, according to Murray Schoonraad, was deeply impressed. 'Tell me now Battiss,' said the Spaniard, 'am I as good as your Bushman artists?'2

Rock Art Composition I and II illustrates an important point as Battiss negotiated the relationship between rock art and modernism. He tirelessly traversed the country to visit well-known rock art sites in the 1930s and copied and traced the images he found on rocks and cave walls, many of which are now housed in the Origins Centre at the University of the Witwatersrand. He also painted rock art scenes in watercolour on paper but, as Marion Arnold has argued, rock art, for Battiss, was typically more a stimulus to modernism than something he imitated. In it, she says, 'he was ready to assimilate alternatives to verisimilitude'.3 Karin Skawran similarly noted that the influence of rock art on Battiss's style is usually seen as a 'highly personal'4 interpretation, or as Andries Walter Oliphant puts it, they were 'individualised re-workings of rock art' in which he synthesised 'technologies and aesthetic ideas of modern European art ranging from Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, Dadaism, Surrealism and various forms of abstraction on the one hand, and the complex visual grammar of rock art on the other'.5

These two works represent neither this modernist approach nor the mimetic scenes of rock art originals. Rather, he has made the leap to the rock-art-inspired flattening of the picture plane so that it is difficult to distinguish which figures represent rock paintings and which might be the artists making them. While remaining more faithful than usual to rock art depictions, this spatial ambiguity represents a 'multi-level reality' that dissolves the distinction between the phenomenal and the spiritual realm and presents "a more conceptual interpretation of reality".6

'Battiss', Oliphant concluded in his contribution to The Gentle Anarchist, 'would not have become the artist he did without the magisterial repository of Southern African rock art which he worked to preserve and promote. His work is not a homage to the past but a signal of the passages South African art in the twentieth century had to negotiate. In this, he opened a path leading from the repressive past to the present and perhaps to the future of creative freedom beyond prejudice and proscription'.7

Rock Art Composition I and II are likely just such a homage, showing Battiss poised between the rock art that provided his inspiration and the radical modernism for which he is so widely recognised.

1 Murray Schoonraad. (1976) Walter Battiss. Cape Town: C. Struik Publishers. Page 11.

2 Ibid., page 16.

3 Marion Arnold. (1989) 'The Spirit of the Picture: Thoughts on the Paintings of Battiss' in Battiss and the Spirit of Place. Pretoria: University of South Africa. Page 40-41.

4 Karin Skawran (ed). (1989) Battiss and the Spirit of Place. Pretoria: University of South Africa. Page 4.

5 Andries Walter Oliphant. (2005) 'Modernity and Aspects of African in the art of Walter Battiss' in Walter Battiss: Gentle Anarchist Johannesburg: Standard Bank Gallery. Page 22.

6 Karin Skawran (ed). (1989) Battiss and the Spirit of Place. Pretoria: University of South Africa. Pages 16 and 17.

7 Andries Walter Oliphant. (2005) 'Modernity and Aspects of African in the art of Walter Battiss' in Walter Battiss: Gentle Anarchist Johannesburg: Standard Bank Gallery. Page 23.