Important South African and International Art

Live Auction, 7 November 2016

Evening Sale

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

signed, dated 1997/8 and inscribed with the title on the reverse

Notes

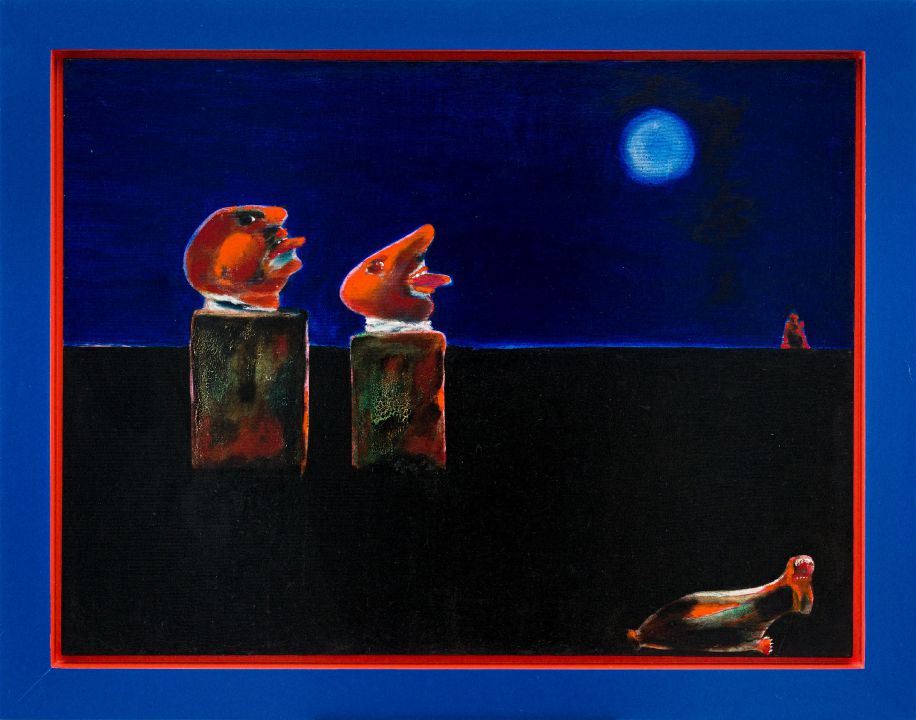

In Howling at the Edge of Dawn, Robert Hodgins, this country's colour-supremo, placed two disembodied heads, both in profile, and both with their tongues lolling out their mouths, yowling at a full, hazy moon. The horizon line, defined with strokes of vaporous blues, and punctuated by an enigmatic marker, splits the canvas in two, while the stone pedestals that support the heads, floating in a midnight-black space and encrusted in thin, dirty reds and faint, emerald greens, suggest a ritualistic or debauched mood. Perhaps the most arresting detail in the painting, however, is the grotesque, crippled form isolated in the bottom right corner that Hodgins lifted directly from the oeuvre of Francis Bacon. The reference might immediately bring to mind Bacon's harrowing and canon-defining series of screaming popes based on Velázquez's portrait of Pope Innocent X, but the form Hodgins chose is more closely related to the Irish-born artist's bleak, breakthrough triptych of Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion that was painted in 1944, and remains a linchpin of the post-War collection at the Tate, London.

Bearing in mind so many of Hodgins's depraved, distorted figures, all painted with restless, vivid marks, it comes as no surprise that Bacon played such a pivotal role in his iconography and style. Evidence of Bacon's influence on the South African is ever-apparent in works such as Ubu Screams (1984), End Game (1994), the record-breaking J'accuse (1995-1996), and Circus: Strongman (2006) - all recently sold at Strauss & Co - and it is worth noting how frequently Hodgins mentioned Bacon in conversation and interviews. On one such occasion, while chatting with William Kentridge and Deborah Bell, Hodgins picked out a selection of Bacon's 'black' pictures, mentioned some of his 'nice bluish-pink limbs', and described them all as 'stunning pictures'.1

Howling at the Edge of Dawn is not simply Hodgins's homage to a painter he loved. The work might borrow directly from Bacon, but it is painted in the South African colourist's unmistakable spirit. Despite the inclusion of the open, screaming mouth in the corner, with its teeth like claws suggesting the existential agony and human vulnerability on which Bacon played, one cannot help but sense the tongue-in-cheek humour that characterizes the best of Hodgins's paintings.

1 Brenda Atkinson (ed). (2002) Robert Hodgins, Cape Town: Tafelberg. Page 52.