South African Art, Jewellery and Decorative Arts

Live Auction, 8 October 2012

Session 3

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

signed

Notes

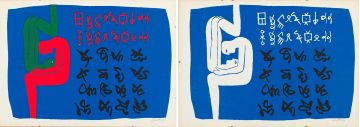

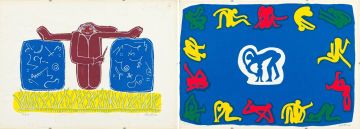

An important part of the art of Walter Battiss is a confluence of specific African and Western pictorial traditions. The Western bequest was passed on to him by local art institutions modelled on European establishments. His African heritage is the bounty of his own research.1

So writes literary, arts and cultural theorist, Professor Andries Oliphant, of an artist whose global vision is perfectly demonstrated in this painting. Battiss acknowledged that his first exposure to rock art in Koffiefontein in the Free State was to shape the content of his 'creative subconscious' for the rest of his life.2 He progressed to in-depth studies of local and international rock art, acknowledged it as a sophisticated art form and published extensively on the subject.

After one of his field trips Battiss wrote:

When I came down from the mountains of initiation I was articulate and free. For I had conversed with the white rocks and lilac trees, the coucal and the rhebuck. I had conversed too with the ancient men of Africa who spoke to me through their picture writings on the walls of their crumbling rock shelters.

The twisted rivers and endless veld spoke of animate and inanimate space.

All this was my peculiar discovery but I had no desire to paint an anecdote about them but rather to make pictures of them in such a way that I exposed the happy change they had worked in me.

Yes, I had made and want to make pictures which are a colour language of the haphazard experiences of my African existence.

These pictures I call fragments of Africa but they are really fragments of myself.3

The effects of rock art on the artist were clearly profound and are amply demonstrated in Five People in a Cave. It was his increasing appreciation of rock art and his exposure to European modernists that enabled him to break with illusionism in pictorial art in favour of an increasing abstraction. Rather than creating a window through which to observe an illusionary world, the painting becomes an arena in which to act.

Painted caves undoubtedly had magical resonances. Figures in motion and wavy lines around a human form may indicate hallucinatory or trance states. Many researchers refer to a powerful being with supernatural powers and a trickster who are central to San cultures. Battiss demarcates areas of the painting for different activities allowing the artist as shaman to engage with worlds beyond the canvas and to guide viewers through diverse experiences. Elevated and aerial viewpoints alternate randomly to disrupt expectations. Figures cavort in a circular motion as if dancing.

Battiss's earlier, more painterly approach gives way here to a greater abstraction that employs simplified figures on clearly defined areas of bold, flat colour. Signifiers like the infinity symbol may have less to do with the geometric forms, abstract designs and patterns that are common in rock engraving sites but may refer to unlimited realms beyond the frame. Rather than fixed meanings, Five People in a Cave draws on multiple traditions. Undoubtedly a key work in Battiss's trajectory from his earlier naturalism towards abstraction, it is a seminal painting in South African art history in that it bridges the shift from modernism to the contemporary.

1. Andries Oliphant, 'Modernity and aspects of Africa in the art of Walter Battiss' in Walter Battiss: Gentle Anarchist, A retrospective exhibition of the works of Walter Whall Battiss (1902 - 1982), Standard Bank, 2005, page 19.

2. Ibid, page 20.

3. Walter Battiss, Fragments of Africa, Red Fawn Press, 1951, unpaginated portfolio.

Provenance

Acquired directly from the artist's son

Exhibited

Standard Bank Gallery, Johannesburg, Walter Battiss Gentle Anarchist, Retrospective, 20 October - 3 December 2005, catalogue page 103, illustrated in colour