South African Art, Jewellery and Decorative Arts

Live Auction, 8 October 2012

Session 3

Incl. Buyer's Premium & VAT

About this Item

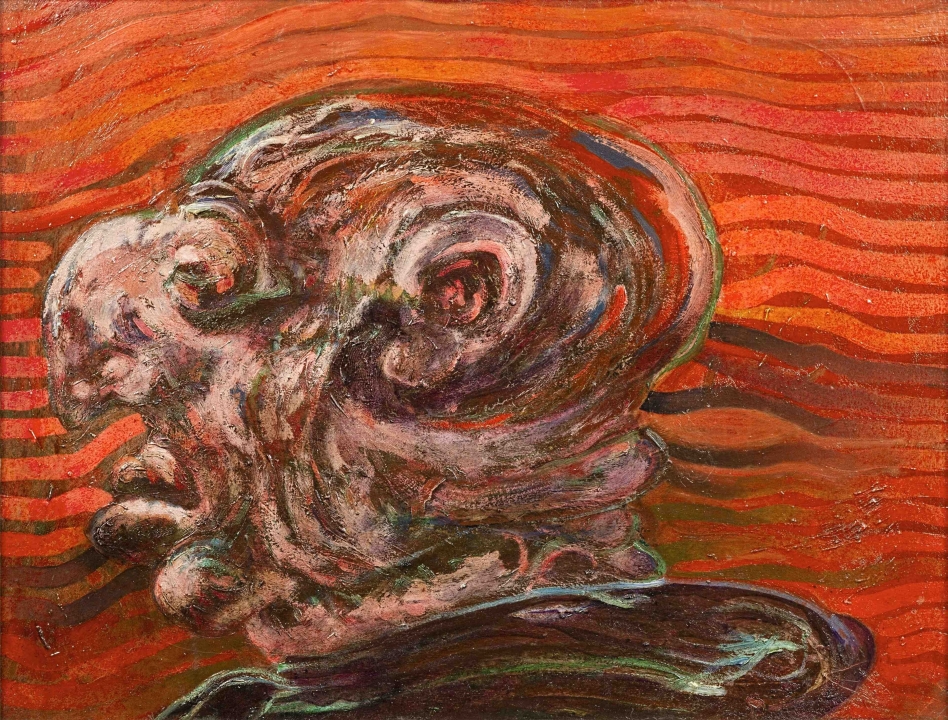

signed, dated 1983 and inscribed with the title on the reverse

Notes

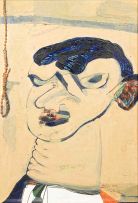

Robert Hodgins's portrait of leading New York art critic, Clement Greenberg, provides extraordinary insight into the man, prevailing art criticism from the 1950s onwards and its continued impact on South African art as well as Hodgins's own attitude to these developments.

Clement Greenberg's influential role in defining mid-twentieth century High Modernism is legendary. Believing that the best avant-garde art was emerging in America rather than Europe after World War II, he is credited with redefining contemporary art, promoting the Abstract Expressionists including Jackson Pollock, the Post-Painterly Abstractionists such as Frank Stella and Colour Field painters like Helen Frankenthaler.

In insisting that the work of art be entirely self-referential and requiring paintings to be true to their media and acknowledge their two-dimensionality without recourse to the artifices of perspective, he was ruthlessly lampooned by popular commentators like Tom Wolfe who had the critic on his knees measuring the flatness of the canvas.

But how many artists, collectors and connoisseurs remember Greenberg's engagement with South Africa? Sue Williamson, in her seminal publication, South African Art Now, outlines events:

In 1975 prominent New York art critic Clement Greenberg was invited by the organizing committee under Dr Sylvia Kaplan to visit and judge the biannual Art South Africa Today exhibition held at the Durban Art Gallery, the city art gallery. Work for this national survey exhibition was selected from an open submission, and local artists were astonished when Greenberg awarded the major prizes to a naturalistic study by Sunday painter Christopher Haw and a crude roadside-style painting of an elephant charging toward the view through a thicket of small mopane bushes. His choices were read largely as a slap in the face, a way of ignoring the more serious work on show, and a mark of Greenberg's contempt for the level of the work he was asked to judge, which he said "lacked authenticity".1

In Clem, Hodgins reveals his attitude to the all-powerful critic. With his large head filling the format, he has all the authority of a Roman Emperor. The acclaimed connoisseur is defined by his considerable nose and imperiously down-turned lips, but his dictatorial judgements are revealed as pompous and questionable through the artist's humorous treatment of the subject.

This painting, more than any other, represents an important moment in both Hodgins's career and South African art history. It underlines the artist's refusal to be defined by prevailing trends, his insistence on artistic freedom to pursue both abstraction and figuration and the right to make choices according to the artist's judgement and not the prescriptive demands of controversial critics.

1. Sue Williamson, South African Art Now, Collins Design, New York, 2009, page 25.

Provenance

A gift from the artist to the current owner